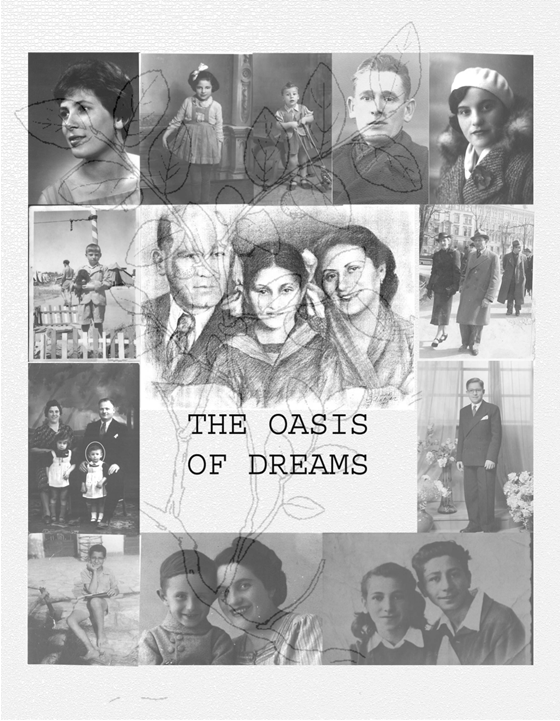

Book.

The Oasis of Dreams

Chapter 3. Children of the Holocaust

Part Two: Who Are We?

Our story is the story of the Generation of the State, the generation forged during the founding of the State of Israel. Two generations of Zionist life in the land of Palestine had preceded ours: the Founding Generation, led by Ben-Gurion, and the Palmach Generation, led by Moshe Dayan and Yigal Allon. The iconic generals Yitzhak Rabin and Ariel Sharon were also groomed in the Palmach days.

We are the Third Generation, born in the thirties and forties. One after another, the pieces of our adolescent landscape unfolded with WWII and the Holocaust, the influx of illegal refugees from occupied Europe, the struggle against the British, the War of Independence, a still more earth-shaking wave of Mizrachi and Ashkenzi immigrants and still further Arab attacks on the newborn state. After the Suez War, in the fifties, our leaders claimed that the era of war had given way to the era of peace. We, of course, took these claims seriously, though they had no basis in reality, so we never considered the army our highest calling – as the Palmach generation had. We pursued other interests, namely: science, business, sports and art. Beyond the communal life of the nation, each of us delved into our own personal experience, and these individual narratives will be presented in full, unvarnished and whole, as without them none of us can truly be known. While the Hadassim tale deals in a miracle, the tales of its students are sometimes quite difficult to bear. Some of our parents were murdered in the Holocaust, while still others fell in the War of Independence. The remainder survived to build the state, handing their flag down to us at the twilight of their days.

Part Two tells the story of that youthful lot, hailing from all over the world, which first gathered together in Hadassim under one banner, and then charged toward their futures with an energy that no other place could have given them.

Chapter Three: Children of the Holocaust

A. The Seemingly Impossible

In order to create the conditions for true dialogue among Hadassim students, in order to stir in them a life of creativity, Jeremiah and Rachel Shapirah determined that students would be selected in equal numbers from three groups: Holocaust survivors, children of broken or troubled homes, and lastly those children of a comparatively privileged status – heirs of comfortable hearths and homes whose parents were simply too busy to tend to them, for a variety of reasons. The three groups integrated well: the rich kids grappled with new realities; the troubled kids were introduced to better realities, and learned in their guts that they could succeed if they would only make the effort; and the holocaust survivors encountered the new, versatile world of a versatile Israeli identity. In the end, these children of the Holocaust became Israelis, while the troubled kids ascended to the elite and the elite learned to live uncorrupted by their privileges.

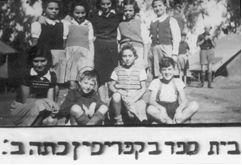

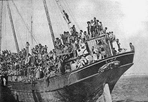

The first eight Holocaust children in August, 1947

Many of the kids in Hadassim who’d lived through the Holocaust were, in fact, the moral and intellectual elite of our generation. Not only had they been better cultivated in the European Diaspora, but their hard-won battles for survival had endowed them with moral and psychological virtues of far greater reach. In order to harness their latent strength, however, they first needed a warm and understanding home; they needed friends who would keep close to them rather than labeling them “soaps” -- a cruel jibe at their near-immolation at the concentration camps – as was so much the custom in the cities and Kibbutzim. They needed teachers who would also be friends.

The children of the Holocaust were given all of these things in Hadassim. The following are some of their stories, starting with Ephraim Shtinkler-Gat and ending with Avigdor Shachan. The majority of their age group hadn’t survived, and those who did carried scars in their souls that compromised their full development. But in Hadassim, Ephraim, Avigdor and their friends did the seemingly impossible.

B. A Child in the Closet

As his parents were being murdered in Auschwitz,1 the five year old Ephraim Shtinkler- Gatwould end up spending two years imprisoned inside a coat-closet in a Polish family’s apartment. It was in that closet that he ate, drank, grappled with lice and breathed naphthalene – all without so much as coughing or sneezing or uttering a single word. He slept with his knees curled up in a sitting position. Whole days and nights he would spend in the dark, motionless, taking in the conversations outside his little sanctuary, listening to the family exchange words with SS agents who would exterminate him within the span of seconds if they but discovered him. These weren’t healthy conditions for a five year old’s development, to say the least. Our estimate is that most children could not survive in such circumstances, and that those who could would remain forever tortured. Not Ephraim.

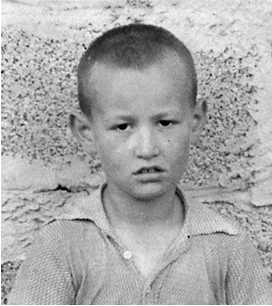

Ephraim Shtinkler-Gat

Most families who risked their lives hiding Jewish children lived in crowded conditions, often sharing a single room with friends, relatives and neighbors. The child, a fugitive from Nazi justice, would usually be kept a secret even from most of these co- inhabitants, as most of them would otherwise have run straight to the Gestapo for sheer bigotry and material gain. Today, there’s hardly a father or a grandfather who would believe that Ephraim sat still and silent over the course of those two years.

Though I’d already read about his background, I could hardly believe my own ears when Ephraim recounted his story. As we sat together in my kitchen in 2005, on a tempestuous winter night, I searched for any sign of a wounded and tortured soul, the kind I would have expected from the war veterans I’d written about all these years. But I found nothing of the kind. Instead, his casual smile evoked something entirely different – as if Hadassim had reduced his childhood trauma to an amusing memory. If this is what happened, I thought to myself, our school’s success had indeed been unparalleled.

Ephraim came with the first eight Holocaust children in August, 1947. It was for them that WIZO celebrated the founding of Hadassim on Normandy.

“It was worth the effort just for him,” Helena Glazer, president of World WIZO told us after reading this chapter in her Tel Aviv office. As she turned page after page, she kept whispering “Unbelievable, unbelievable…” as she wiped tears off her face.

And there were many like him to arrive at Hadassim. He was a pale, blond child with brown eyes and Slavic features – handsome, in short – who seemed to have emotionally distanced himself from his past, who seemed ready to embrace life (“we have everything to look forward to!”). It might have been his DNA, it might have been the closet that been his abode, and it was probably also the immediate influence of Rachel and Jeremiah’s educational ideology, which encouraged us to embrace the future. He was alive by dint of his hair color and facial features, by dint of a Polish family’s superstition -- that Jesus had commanded them to save a Jewish boy at their doorstep from certain death.

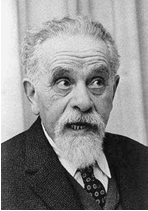

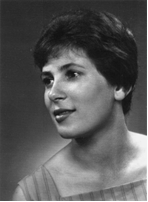

Elena Glazer, president of World WIZO

He remained alive by sheer discipline and plenty of luck.

It occurred to me that luck – or fate, more precisely – was the name of the game that God had played with us in the years 1939-1945. Though Einstein could never accept notion that “God plays dice with the universe,” it became clear in the middle of the 20th century that our maker was doing just that – with a vengeance. The Holocaust finally ended for Ephraim when he was seven years old, parentless, illiterate, his childhood so far eviscerated. Yet he had gained incomparable survival insights. He’d conversed with spiders, learning the lessons of endurance from them, learning to depend on his own mind, to ignore open wounds and not to scratch the scarred-over ones. Hadassim taught him to let the scars go.

Avinoam Kaplan was his first instructor. The first time Kaplan met with the eight children he showed them a bunch of small animals, pulling them out of his pockets one by one, including spiders. “These are my best friends,” Ephraim yelled out, and Kaplan chuckled because he thought the boy was making some kind of a joke. Kaplan would later tell us that he loved Ephraim as a son, and this is also one of Hadassim’s miracles: teachers were to their students as parents.

While we were serving in a paratrooper unit together, I once asked Ephraim how he survived the Holocaust.

“That’s a long story,” he answered. “Well, I have time.”

“Then use it for more constructive things.” “Like what, for instance?”

“To make plans for your vacation.”

While we were growing up together, Ephraim thought it better not to tell his story, that there were more “productive” things to be getting on with. Now, at the age of 68, his edge softened a bit, he was more willing to explore his earliest trials. I was so grateful that I wanted to hug him, but I was afraid that even that would cut the conversation off very quickly.

Who would have believed that this Holocaust orphan could serve in one of the finest battalions, that he could spill blood with his brothers in ‘67 and ‘73, that he would go on to take a bachelor’s in chemistry and biology and master’s in botany (in Kaplan’s footsteps), that he would then study computer science and attain a senior position within the sophist icated Israeli aviation industry? It was men like Ephraim, born of the Holocaust but bred in Hadassim, that allowed the Israeli state to endure the multiple threats against her.

After our first interview with him, we called him to go over certain detai ls regarding his childhood survival. “How are you doing?” We asked.

“Couldn’t be better!”

Was he exaggerating? Was it possible he was merely hiding behind psychological fortifications? To our eyes, Ephraim had always embodied the “nice Israeli” archetype. We asked him how Hadassim had helped him, how he made the transition to the “normal” Israeli persona.

“We came into an atmosphere where the past was dead, where we were now reborn in our true homeland. Almost nothing was said in Hadassim about the “thing” that happened. During the Holocaust, everything was forbidden (except some very limited things) but in Hadassim everything was permitted (except that which was forbidden). So almost overnight we found ourselves in unadulterated freedom, something that even normal children rarely experience. That freedom neutralized the otherwise inevitable compulsions and fears -- of the unknown, of trying new things – that children of our backgrounds would have. Unfortunately not many other survivors were so lucky. The nurturing and encouragement we received at the get-go from our first counselor, Malka Kashtan, helped us a great deal.”

It is astounding, and telling of Hadassim’s magic, that a Tel-Avivian bourgeoisie accustomed to thrice-weekly hair-treatments from her mother became a mother in her own right to these eight Polish children. Her care taught them that it was possible to bond with fellow human beings, something they’d never learned in all their constant dislocations before and after the war. Malka also looked after us, the native Israelis, for a whole year, and was able to give many of those with troubled family backgrounds – Gideon Ariel, Asher Barnea, Shula Druker, Esther Korkidi and others – the same level of care and psychological security. The dialogic educational concept was given a personal dimension through her. Sadly, at the age of eighty-four, her daily routine is now sealed inside her house; having survived her husband and even her two daughters, she only waits for her own death. We sense, with heavy hearts, that her kindnesses have gone unrewarded.

Ephraim was born in 1938, in the city of Bielsko-Biala in West Galicia – the birth-place of Arthur Schnabel, the same Jewish pianist whose performance of the “Phoenix” Beethoven sonata so enraptured us on that magical Tikun Leil Shavuot night. Dr. Michael Berkowtiz, an assistant of Theodor Herzl and the Hebrew translator of his book Der Judenstaat (“The Jewish State”), was a high-school religion instructor in Bielsko-Biala in the years 1911-1934. He was one of the main transmitters for the Herzl Effect on Judaism2 , and his influence in the city is crucial to understanding the story of Ephraim Shtinkler-Gat.

The city of Bielsko-Biala was a fusion of two elements divided by the Biala River. Jews had settled there from the 17th century; their population had exceeded 4000 by WWII, and Zionism had flourished there since the end of the 19th century. Besides Arthur Schnabel, other well-known Jews native to the city included Zelma Kurtz, one of the more renowned European Divas tutored under Gustav Mahler’s baton in the Vienna State Opera; Herman Freishler, director of the Vienna Volksoper; and Jan Smeterlin, another accomplished pianist and Chopin interpreter. Thus, before the war Bielsko-Biala was a city of great culture, its high cosmopolitan threshold touching on the life of Jews and Poles equally, rich and poor. The baby Ephraim breathed it all in despite his modest roots (his father was a blacksmith) and working-class heritage – a heritage that proved potent indeed when it came time for him to survive in that wretched closet.

The Germans conquered the region encompassing Bielsko -Biala on the third day of the war, and two weeks later they had already burned the synagogues and looted the Jewish shops.3

Ephraim was the only child of Yaakov and Sara. He has only one genuine memory of the town: his father walking along with him as he showed him how to ride a bike. In 1941, his family moved to Zawiercie to live with his grandfather.

Ephraim remembers the train-ride – the depressed passengers, their terror-stricken eyes longing to be both invisible and blind.

Yaakov and Sara Shtinkler

The Shtinklers resided in the Jewish quarter of Zawiercie. In 1942 the Jewish quarter was converted into a ghetto, a kind of prelude to extermination, whose inhabitants needed permission to exit. Luckily Yaakov, a resourceful and self-sufficient man who by now owned his own smithy in the Polish worker’s quarter, had such permission. He’d also befriended the Novak’s, a family that lived above his workshop, and did many of their house repairs for free. He told them all about his sharp-witted and lively young son.

Ephraim’s father dedicated all his energy to save him. The Novak’s had fallen in love with the boy before they even met him. Ephraim would soon learn that life and death can hinge on the power of the tongue at these moments.

Ephraim told us his first memory of the Ghetto:

“My father and I were directed to one group, my mother to another, with a road separating the two. My mother was chosen for the group that was to be exterminated.

But she found the strength to approach one of the officers and ask to be allowed to join us and live, and he agreed, though it was probably a one in a million chance that he did.

Mother got an extension on her life, while the others were sent away to be swallowed up by the earth. Not everything in life is black or white; there are hues of grey and dark brown, and in hell the grey stands for light and brown can mean salvation.”

His second memory:

“We lived on the ground floor in the Ghetto. I remember lying on the bed, surrounded by chairs to prevent me from falling or bother my mom while she was doing house cleaning. I heard her washing the floors and singing in Polish, ‘All the fish are sleeping in the lake, though you are still awake…’ To this day I hum that song, always picturing her luminous face. As she kept cleaning I imagined to myself that she was a queen and that we would soon fly off back to King Boris’ palace.”

Yaakov Shtinkler

“Why didn’t your parents try to rebel?” We asked.

“I can’t really answer for my parents, but the kids were mesmerized by the soldiers’ obvious power, their imposing and always neatly-ironed uniforms, their organization and efficiency. They commanded, and everyone obeyed instinctively.”

“So the German were allowed to murder and people did nothing? How could you let that happen?”

“All of us, the ‘good’ kids, we all believed that if we could do what was demanded of us they would keep us alive. We felt guilty, like we had all done something wrong; we never thought of hurling stones at them the way the Palestinians do today – we lacked that sense of justice, the kind that motivates you for action. Guilt only allows for resignation. We felt guilty, so we were powerless – and they were strong.”

I’ve always asked myself: Who is to blame for the inherent weakness that allowed for the Jews to be eaten alive? What could bring on a sense of guilt that would let the Nazis destroy with impunity? And the answer: Jewish leaders, ever busy poring over the Torah and raising capital, had deserted their communities and come to Israel to build and be built up into a nation-state. In that dire moment of history, European Jewry needed the right leadership to fight guiltlessl y and ferociously. Thus, what was tantamount to mass suicide was both the price of Judaism and of Zionism. The occupation zones were unlikely sources of rebellion in any case, given the general anti-Semitism of the native residents, who were at the very least going to be unwitting participants in the slaughter. They would neither assist any uprising nor lift a finger to deter the Germans from brutal retaliation, nor admit too many Jews into their partisan (resistance) fold in the surrounding forests.

On the other hand, there were many individual acts of rebellion, many of them life-saving. Ephraim’s life was preserved by such a rebellion, by his father’s. Shevach Weiss, Metuka and Alex Orlander, Eliza Bar-Shwartzwald and Moshe Fromin were all promised a new life in Israel by such rebellions.

In August 1943, there were six thousand Jews in the Zawiercie Ghetto. The Germans eventually sent everyone they could get their hands on to Auschwitz, among them Rabbi Shlomo Rabinovitch, the last great rabbi of the town. Rumors of the liquidation began to spread the day before, specifically that the Germans were going to be killing a certain number of the children.

Yaakov acted quickly to save his son. His own, quiet rebellion called for him to enlist his new Polish friends. Franchise Novak agreed to send his two daughters Rosalia and Wislava out to the Ghetto’s border at a pre-arranged time, where they would pretend to busy themselves in games and wait for Ephraim. Once they recognized him, in his prearranged clothes, it was simply a matter of letting him into the game as casually as possible. Then they slowly moved back toward the workshop, careful not to alert any of the policemen – just two little girls and an even younger boy, strolling and giggling innocently together. It was a simple plan, and it worked brilliantly.

Franchise Novak

While the girls climbed back up to their apartment, Ephraim locked himself inside the smithy, where the darkness was complete. He sat on a lathe and softly hummed his mother’s song about the little fish sleeping in the lake, thinking of his parents as knight and queen. The Novak felt so much pity for the five year old, immersed in machinery and dust, that they risked their own lives sneaking him up the serpentine stairway up to their apartment. “There are Christians who want the Jews to suffer for the murder of Jesus, and then there are those who wish them salvation. The Novak’s belonged to the second group,” Ephraim told us.

The day after, when Yaakov confirmed that his son was alright, he decided to find somewhere even safer for him and asked the Novak’s to keep him for another 24 hours. Unfortunately, Yaakov didn’t know at that point that he didn’t have 24 hours: the Germans chose the same day for their “liquidation,” and Ya akov and Sara Shtinkler were both sent to Auschwitz. Only eight Jews remained in the Zawiercie Ghetto, two of them children. Ephraim was one of them.

[Ephraim]:

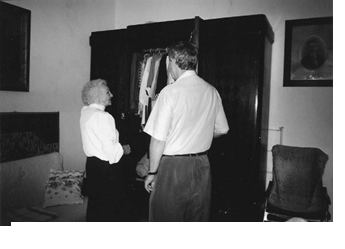

The entrance to the Novak’s house was through the kitchen, which led to the sparsest living room. The only bathrooms were in the courtyard, and since there weren’t any showers everyone was obliged to wash themselves in a large bucket. The living room had enough room for one bed (and a closet), for the parents, Franchisek and Genovepa, and two of the girls, while Genovepa’s mother and her dwarf sister slept in the kitchen. So besides me, kindly relegated to the eighty centimeters in the closet, there were six people altogether. I knew very well that the Germans would kill me in an instant, that I had to keep quiet even to the point of repressing the dimmest sneeze or cough, that the neighbors who strolled in day and night could just as easily turn everyone over to the authorities. That sustained condition dictated the next two years for me and my tiny capsule, disconnected from day and night. Still, I began to experience something akin to meditation, without either boredom or anxiety; I stopped asking when all of this would end, when evening or the next meal would come.

Regardless, I was very attentive to all the goings-on in the apartment. I tensed up whenever I heard a strange voice, or whenever a neighbor came by, and I kept as silent as mouse. None of that had to be explained to me. I was only allowed to relieve myself at night, when I would be rushed out of the closet to get cleaned up and then pushed back inside just as quickly. On one occasion, they’d taken me out to treat me for lice, when there was a sudden knock on the door that sent me back into the closet trembling and naked. Wislava threw herself into the bucket in my place, tearing her clothes off just in time for the neighbor to stroll in complaining about being made to wait in the hallway.

As far as I was concerned, this situation could have gone on forever. Franchisek took seriously ill after a short while, and no amount of cupping his chest with hot glasses could help him without any other available level of care.

He lay dying on the bed surrounded by candlelight for four days, and I kept breathlessly still in my little closet space as all manner of friends and neighbors came in to say their goodbyes. Without a breadwinner, it was left to Rosalia and Wislava to support the family, including me. So everyday they marched to the nearby village, where they could get milk and eggs for cheap and then sell them back for a profit in town. As young as they were, they still kept quiet about me – even with their closest friends.

Two months before the Russian occupation, the Nazis appropriated the living room for two of its officers, and the family was moved into the kitchen, where I soon joined them -- covered by the sliver of cloth that hung around the dinner table. I sat there day and night on a low bench, where I could gaze at the officers’ feet as they took their meals.

The closet

As Russian soldiers replaced Germans, Ephraim was finally allowed out of the closet. He was every bit as illiterate as the mythical boys raised by Roman wolves, yet he still had the gleam in his eye of his native city’s culture, one that remained with him always. Genovepa, now a widow, smuggled him to her sister-in-law’s in a nearby town for two weeks. The Novak’s were afraid they had taken too great a risk even with their neighbors’ lives, though Ephraim was now well-versed in the proper Christian prayers and rituals and could probably pass for a common Polish boy.

He was now seven years old. After another several months, Genovepa met another Jewish survivor, a factory owner, and told him about the boy she had hidden for two years. When he came to visit, the man suggested that they send Ephraim to a Jewish orphanage, and the boy was soon traveling the escape routes, stopping in one of the refugee camps (where he briefly met Shevach Weiss) on the way to the children’s camp in Furten, Germany. There, one of the instructors, Masha Zarivetch, promised him that he would soon “reach Eretz Israel and be reborn in a new paradise.”

Masha and Eizik Zarivetch eventually came to live in Hadassim. On our first Holocaust Memorial Day, Eizik told us all about life at the Furten camp, and one of the other sabras (native Israelis) remarked, “So the Holocaust wasn’t so bad, then.” To which Eizik replied, “Furten was heaven compared to what this boy had to endure,” nodding toward Ephraim. He turned to him and asked i f he might tell his story. Ephraim looked up at him and went deathly silent.

C. Kneeling at Mary’s Feet

Elisa Shwartzwald-Bar was one of the orphans to arrive with the first eight children to Hadassim. She was born in 1938 in Lvov, the capital of Galicia,4 known as a “Paragon of Beauty” in Jewish parlance. Jews had been in Lvov since the 13th century; there were 150,000 of them there – a full third of the city’s population – up until the Holocaust. When the war erupted, the Soviet Union annexed the city to the Soviet Republic of Ukraine and took freely of its possessions, while the Germans would end up taking the rest when they came in July of 1941.

Elisa Shwartzwald-Bar

Elisa was the single daughter of a wealthy and established merchant family; she was two years old when the Germans occupied the city. As she recounts her first memory of it, “the Germans burst into the house and tore all the pictures out of their frames, tossing everything into chaotic piles and marking a bold X on every item worth looting.”

The family was thrown into the Ghetto in November, 1941, and from that day her father, Randolph, did everything he could to save her. For anyone who would doubt that a two year old girl could remember these things, we answer that no one was left to recount them to her: her parents and remaining close family were exterminated to the last man.

Elisa would go on to spend twelve years in Hadassim. “Hadassim’s strength owed itself to people’s immense energies, far more than the usual, in every field.” As she put it to us, remembering back fifty years, “They invested everything they had in us – they didn’t hold back, they were absolutely reckless about it – and asked nothing in return. They poured all their strength into us. Life in a boarding school can be like that, it can serve as a social laboratory for collective action. The combination of that commitment with that environment had an indelible effect on us.”

Elisa Shwartzwald- Bar

After graduating from a teachers’ seminary in Hadassim, Elisa went on to do a bachelors in Bible Studies and Literature and then a master’s in education at the Hebrew University. Today she works at the Council for the Sheltered Child in Israel, helping to rehabilitate some 550 children of broken homes, ages K-3, 92% of whom passed exams in reading and math with better scores than the current 8th grade national averages. “The only relative I have left, a very distant one, used to tell me I’d end up as a seamstress. But for Hadassim, he could easily have been proven right.”

Elisa remembers:

“Part of our family was smuggled out of the Ghetto to live with a Polish family. They’d received a handsome sum from my father in exchange for housing us, but the neighborhood Ukrainians, even more than the Germans, were always spying after families that sheltered Jews, were always suspicious that someone buying extra groceries could be a Jew-lover. So eventually the Poles threw us out, and we scattered about the town at night, my aunt Berta and I, knocking on doors and looking for shelter. For a while no one would let us in, and with fear ruling the streets, my aunt, in an act of desperation, left me behind in one of the back rooms of the house we’d been thrown out of. Fortunately, our Polish hosts discovered me in the morning and decided to keep me anyway. They were too devout to get rid of me. Father would send them more money from time to time, and eventually they saw that they could keep me openly – I was blond, had blue eyes and spoke Polish well enough, so it was easy for them to pretend I was their granddaughter.”

“Father made a few rare, nightly visits, always bringing more money and occasionally leaving me brief notes. One of them read: ‘Remember that your name is Elisa Shwartzwald, a Jew. Tell no one, but always remember.’ We lost contact toward the end of the war, and I assume he was probably caught and murdered.

“During that period of shelter, I learned all the Christian practices and accompanied my hosts to church. They even gave me their surname, though I can’t remember it today. The only friends I had were the few mice who would eagerly await my daily portion of yellow bread. I used to hide the leftovers underneath the sofa in the bedroom, then lie in the dark and listen to them twitter about underneath as they ate it up. I can hardly remember it ever being cold, really – I remember only the bountiful summer gardens, the wonderful pea pods and poppies. The Germans came to the house from time to time, but never suspected I could be a Jew. I was still very afraid, of the planes and bombs, of the secret I had to carry with me that I hardly even understood.”

Only eight thousand remained of the original 150,000 Jews of Lvov after the German occupation. The rest were dispensed with in the Janovsky and Belzec death camps5.

When the occupation had ended, Elisa’s caretakers kept expecting someone to come for her, but they waited in vain. Despite everything, they’d never really bonded with her; it was clear they had tended to her from religious and material motives. Now they were desperate to escape west, away from the Soviet occupied zones, so they sent Elisa to the Jewish community center where most of the effort to reunite families was concentrated.

So there she was, a six year old girl sitting alone, listening to reams of Yiddish gibberish passing wildly from one pathetic face to another, waiting politely for someone in the crowd to recognize her. Finally, a woman came to her and asked, “Can you give me any names of relatives? Any name you can think of.” Elisa gave her one name that was familiar, ‘Mandel,’ and the lady sent a note on her behalf to the family listed under that name. Elisa’s Polish caretaker took her to their address in the city, and as luck would have it they identified her immediately. That was the last Elisa saw of her Polish hosts.

The Mandels were distant relatives, and they gladly adopted her. Curiously, she continued to attend church in secret. When they asked where she was spending that time, she told them she’d gone out to play. They had their own suspicions after a while, though, and one day when she gave the same alibi they laughed and said, “Nah, you were seen in church, kneeling at Mary’s feet and praying to the icons! Don’t you know you’re Jewish? You don’t have to go there anymore.”

Soon enough, the Mandels were off wandering through Poland themselves to escape from the Soviets. They finally stopped at Lignitz, where Elisa met Metuka.

Sixty years later, the little blond Jewish girl who knelt at Mary’s feet in a Polish church is a senior officer of Israel’s educational system -- another Hadassim miracle.

D. “It is God’s Hand”

Alex Orlander was born in 1935, near Lvov in the town of Zolkiew6 in Eastern Galicia. His sister, Metuka, was born four and half years later. Their mother, Rachel, came from one of the richest families in the area, the Reitzfeld’s, who owned a nearby oil and barley factory. Their father, Hirsh Leib, orphaned at a tender age, was a successful fur manufacturer – and Zolkiew was the center for Poland’s fur industry, center of fur manufacturing for the whole world. Hirsh’s aunt had adopted him and he had learned the fur business from his cousin.

The big guns of the industry were all mostly Jews, in fact. Prior to the war, many of them had taken their commerce to Paris, London and Brussels, quickly flourishing there and maintaining their network throughout Europe. But Zolkiew remained the nexus of activity in this line; its furs could be found in the most elegant shops in every capital of the world. Metuka would certainly have enjoyed this facet of life herself – and Alex would certainly have risen up in the business – were it not for the war.

Zolkiew was originally built as a fortress in the sixteenth century. There were Jews there from the beginning, and by the 19th century the Jewish community had built its central synagogue there with contributions from rich Spanish Jews. True to the city’s origin, the synagogue was actually planned as a citadel for Jews in times of invasion or war – a prescient notion, no doubt, but one that fell short of the right conclusion: a national homeland in Israel. A “Soldier’s home” based on a model of the Zolkiew synagogue was built in Beer Sheva by David Tuvyahu, a former resident of the Polish city, to keep the tradition alive.

Alex Orlander and his sister, Metuka

The composer of the Israeli national anthem, Naphtali Herz Imber, was born in Zolkiew in 1856. The famous Yiddish poet Moshe Leib Halpern was born there thirty years later. Zolkiew saw the birth of the Jewish-American poet, playwright and chemistry Nobel laureate for 1981, Ronald Hoffmann in 1937. The city was home to 5000 Jews at the outset of the war. Nobody then believed – certainly not the Reitzfelds or the Orlanders – that there was a safer or more pleasant place to live. Nevertheless, the city was full of Zionist activity; Alex and his uncle Manek (Rachel’s brother) both tried incessantly to persuade their rich grandfather of buying land in Eretz Israel and directing some of his assets there. A conservative businessman par excellence, he rejected the idea with a charitable smile. Sometimes it is the naïve, not the canny, who are in the right.

The Orlanders lived comfortably in the countryside. Their estate at the city’s periphery was ensconced in orchards and gardens. It was the ideal life that Rachel and Hirsh Leib had wished for their children, one that Alex nostalgically pines for seventy years later – the explosion of happy summers, the excitement of picking fruit off neighbors’ trees. He was rather hyperactive as a child in Zolkiew, but the overspill of energy became initiative as he became a man in Hadassim and an officer in the IDF.

After the army he became a businessman, and he has remained a successful one – affirming the tenacity of his grandfather’s genes.

The Reitzfelds had always lived in prosperity, and Rachel herself was a benevolent and loving hostess and homemaker, always providing a joyful atmosphere. Both she and Hirsh had believed that God would take care of them and theirs. It was an infectious, steady loyalty to happiness, and even after sixty years, in spite of what they endured in the Holocaust, Alex and Metuka, along with their children and grandchildren, are still as optimistic and open-hearted, and just as generous with their guests. We interviewed both of them several times for long hours, and we feel that their story is a microcosm of Hadassim’s success. We felt that their story is Hadassim’s Success story. Both of them have affirmed this last, and encouraged us to make clear that very little would have been left of them without Hadassim.

Several days into the war, the Orlander’s welcomed several relatives who were escaping from Krakow into their home. Despite the nature of the visit, the atmosphere in the house was stubbornly happy and even light. With the din of war in the background, they actually played cards.

Metuka

No one saw the writing on the wall; no one even spoke of trying to escape, of finding real shelter from what history had promised all these years. They’d all thought of Uncle Manek, always harping about moving to Israel, as adorably neurotic. Sure, the Soviet border wasn’t far, but the Russians were easily dismissed as philistines, but the implications of the combined German and Ukrainian attacks against the Jews of Zolkiew, in September 1939, seems to have been utterly lost on this family. It should have been clear what was waiting for them if German and Ukrainian anti-Semitism would join forces.

The Germans turned the city over to the Soviets after only five days. “It was then that the population really began to feel the war,” Alex remembers. Members of the communist party, some of them Jews, readily handed the Russians the names of all wealthy citizens; relatives denounced relatives, each hoping to bring about utopia. Everyone of substantial wealth was arrested, and by June of 1940 most of them were exiled in Uzbekistan. These included many members of the Reitzfeld family – the grandfather, the aging pater familias, included.

This prefatory exile seemed catastrophic, of course. But in the end, many of the exiled survived while most of those left behind in the city did not. With the Germans pressing against the Soviet Union in June 1941, many Jews fled east alongside the Russians. But the Reitzfelds and Orlanders stayed in the city.

On June 28, the Germans occupied Zolkiew, and by the next day they had already burned down its ancient synagogue. The mass abduction of Jews for forced labor began after a month, once they were properly sealed and helpless – and still they didn’t realize what was going on, not fully. “It was common to hear that the ‘barbarians’ who had come in initially and exiled the rich were gone, that our German captors, the ‘civilized Germans’ had taken their place, and once Romanian allies entered the city some people thought we were saved. They [the Romanians] brought lemons with them, and we even bought lemons from them in exchange for food! Then the Gestapo arrived, and slowly rumors descended that they were going to kill Jews. As it turned out, there were no murders in the city, and people continued their lives, but trains were passing through, transporting Jews to the Belzec camp which wasn’t far. Some of them had been able to jump from the trains, and they started telling stories of horrible cruelty and random murder in the outlying villages. My cousin Clara and some of her friends knew first aid, so they treated some of these people. Mother had just then bought a cow for the family, so we’d have more milk for the kids.

“When the Germans began fighting Russia, Father was recruited into a Soviet Polish unit, and we eventually heard that he’d died near Ternopol, eastward toward the Soviet border.”

As German actions became frequent in the city, with Jews butchered in plain sight and others sent to the extermination camps, sixteen people from the Patrontch, Melman and Reitzfeld families holed up together under the Melman residence. But they refused to have Rachel, Alex and Metuka with them for fear that the two year old Metuka wouldn’t hold still and silent and that they would all be exposed. The three of them were therefore forced to leave and move in with Aunt Cohen in the Ghetto at the end of 1941.

Overpopulation in the Ghetto eventually spread plague – typhoid fever – and the rate was atrocious, with one tenth of the population succumbing every day. Cousin Akiva lay dying right before our eyes, and then their mother’s condition began to deteriorate as well. Aunt Sara snuck out of the Melmans’ hole and came into the Ghetto temporarily to help her. Thankfully, Rachel soon recovered and the three of them moved into the Ghetto center to avoid the epidemic.

Metuka: “On my fourth birthday, April 3, mother went out with uncle Joseph searching for food, so that we would at least have something to eat on my birthday. My eyes followed her from behind the shutters. Most of the Jews had already been murdered at that point, or sent to the camps. Mother probably also intended to go and consult with her family on how to rescue us from this inferno, but along the way suddenly German cars burst through the streets and started shooting in all directions. It was one of their tricks: baiting with an announcement of food supplies, then switching once the Jews had crawled out from their hiding places. They drew them in and then shot them wholesale. This is what it meant, their ‘Judenrein’ – Jew cleansing. Some were killed right there in the streets, while others, some 3000 of them, were taken to the Borek Forest to be shot to death. The Germans left about sixty of them alive, my mother and uncle among them, to ‘clean’ the streets.

“Two days later, in the evening, mother and Joseph finally tried to come back to our hiding place, but they were captured and executed almost immediately. I didn’t see them hurt, but the sound of the bullets still pierce and echo in my ears to this day. Alex and I were left alone in the attic. He was seven years old, and I four.”

David Maneck was still busy along with fifty or so others in cleaning the Ghetto and carrying out corpses. After two days, he managed to sneak up the attic and tell the two children that “Mama will be back in a few days,” and leave them some food. Several days later, on a Sunday morning, he led them out to the Ghetto gates. He instructed Alex to walk hand in hand with Metuka to his friend Igor Melman’s house, where they would meet Valenti Back7 and ask for Aunt Sara.

So on they walked on the main road, and as it was indeed Sunday most of the Poles and Ukrainians, who were quite religious, were busy praying inside their churches, allowing for them to cross the city safely back to the Melman house. Metuka remembers every little detail of this trip:

“People in all manner of austere clothes were walking past us in the other direction; various higher-class Poles could be seen riding their carriages. I asked David Maneck, years later, if any of this had really happened or I’d dreamt it all. He told me,

‘No, you weren’t dreaming at all. Your only chance of getting past the Gestapo was that Sunday, when everyone was at church.’”

Valenti recognized Alex and Metuka as soon as he opened the door, and he was genuinely shocked. It was only a year since he’d refused to have Rachel and her children under his house, and her death was now clearly on his conscience. “What are you doing here?” he asked tentatively.

“We know that Aunt Sara is here. Can we see her?”

Valenti pulled the children inside quickly, before any of the neighbors could notice, and he repeated his warning to Alex that Metuka would not be allowed to stay – that she couldn’t be trusted to stay silent. Alex already seemed to know what he would say. “I’m almost a man now. I’ll leave and join the resistance in the forest, so she can take my place. Please – just let her stay in the house.”

Valenti was expectedly moved by this. It was an astounding gesture, an unheard of thing for a boy of seven. So he took them both into the attic, handed them toys belonging to the Melman children, and then left them to talk to the family in the burrow.

“Are you willing to have these children?” The families then held a long discussion, culminating in a disgraceful majority vote to the effect that it would be too dangerous to take Alex and Metuka in – that they should be sent away. It was left to a Pole of German ancestry – an unimaginable reversal of fate – to persuade them: “These children found their way here from all the way back in the center of town; no one saw them, no one harmed them. I tell you, it is God’s hand in this. Only God could decide to allow them here, it is his command. Therefore, as the owner of the house I veto your decision. They stay.” Then he brought Clara and Sara up to the attic, where they washed the two children, cut their hair off and led them back down where they joined the other dwellers. Their number had now grown to eighteen.

It was very soon afterwards that major catastrophe took place: a fire had spread through some twenty houses, and whole blocks were incinerated, including the nearby oil refinery. The Melman’s roof started burning, and as more and more smoke seeped into the house the residents began to suffocate. While their lives were in danger inside, their fates were equally vulnerable outside, where neighbors could easily spot them and report them to the Gestapo. Luckily the house had extra underground sanctuary built at the start of the war, and only a wall separated them from this additional space. As the smoke grew denser everyone clawed harder at the wall, looking for a loose opening they could pry through. One of the girls, a fourteen year old girl by the name of Manya, couldn’t take the panic, and she decided to leave the house altogether. She ran upstairs and out to the courtyard, where she cried back, “Father, I won’t be buried alive – I want to live!” The fire was extinguished shortly thereafter, but for Manya it was too late. She had already run out to the street from the courtyard, where some of her old peers from school identified her. When the Gestapo got wind of it, she was arrested and taken to their headquarters, where she was interrogated and tortured – but she revealed nothing about the location of the burrow or its inhabitants. She died, of course, but her loyalty inspired fierce rebellion in the other prisoners. “These soldiers are nothing but dogs – you can talk, but they’ll murder you anyway…”

On July 10, 1942, two months after Alex and Metuka were accepted into the burrow underneath the Melman house, the Germans ended their liquidation of the Zolkiew labor camp and finished off the remaining forty prisoners in the nearby forest. The hunt continued for the last scattered remains of Zolkiew’s Jews, with the last victims executed on the grounds of ancient Jewish cemetery. It was with this ultimate desecration that the Nazis declared the city “Judenrein”.

The burrow and its dwellers, however, were still intact. There were four young children there now, including Alex and Metuka. Clara entertained them by drawing comical stick figures on newspapers, which they clipped out and goofed around with. She taught Alex how to read Polish, and eventually began reading all the books the families had brought down with them, along with those that Valenti occasionally smuggled in.

As for Valenti, his incessant drinking became worrisome. He worked at a local police station, so there was ample reason to suspect he could let something slip if he wasn’t careful with his Vodka. He even had his colleagues over at the house for weekly card games, in order to buy their trust. Local policemen and Gestapo men played gin and drank to their hearts’ content while Alex and Metuka listened silently, inches below their feet. Some of them would occasionally stay the night, and towards the end of the war the authorities even appropriated part of the house for two of its soldiers. One of the latter was in charge of the nearby train station that saw the transport of Jews to the Belzec camp.

One of the things Valenti smuggled into the burrow was a globe, which the children could use to follow the course of the war while listening to BBC broadcasts through their ceiling. “Eretz Isreal was a frequent topic of discussion for us at the time,” Metuka remembers. “Many of the adults argued bitterly about what the Jews might have been able to do if they’d only had a state of their own prior to the war.”

On July 27, after days of constant bombardment, the Soviets finally entered the city. Some of the bombs and shells had exploded very close to the Melman house. Metuka describes it:

“Shells were blasting heavily outside, and many were dying. I remember thinking how unbelievable it was that we could die now from some random explosion, after having made it this far. The only thing I wanted and looked forward to was a big slice of bread covered in butter and jam; it’s all I could picture to myself now.

“Suddenly, there was dead silence. Valenti knocked on the burrow entrance and we let him in. ‘The Russian are here. You’re free…’

“We were stunned. It just didn’t seem possible, it couldn’t be happening – and we were hesitant to move at first. We waited another half-day to make sure it was really safe enough. The adults could hardly even move, as their muscles had atrophied after all this time. The light outside was piercing white. My eyes went straight to the Katopiski flower – big and yellow, smooth as silk on the inside and shaped like a duck’s beak. I’d hardly remembered that there could be something so beautiful out there in the world.”

Metuka, born and plucked away from her mother in springtime, had only discovered the real wonders of spring at the age of five. And yet, she would go on to live through eleven years of uninterrupted spring in the paradise of Hadassim. There she blossomed like the flower she was destined to become, and took flight as the prima ballerina of the dancing troupe. That was the nature of Hadassim: a school in the mold of a rising Phoenix.

Only five thousand were left of what had originally been seventy-thousand Jews. Ukrainian gangs now took to wandering the streets at night and fell upon the survivors, while Russian soldiers could be seen taking freely and cruelly of defenseless women. It was an expression of the new regime’s hostility, a regime that felt every bit as comfortable dealing in violence. Mass expropriation of homes and possession, along with implacable intolerance toward any criticism, was the order of the day.

Valenti couldn’t hold back his reams of obscenity at the soldiers who had come to strip bare the Melman house. He was immediately arrested and sentenced to death, and he fell to the ground pleading for his life. When his claims to have saved Jews during the war fell on deaf ears, Metuka and Alex came running to help him. The commander’s heart softened at such a display from the children, and Valenti was released. He subsequently took his family west away from Soviet territory.

In 1945, when the whole region was formally annexed to the Soviet Union, Alex and Metuka, along with the rest of the families, found their way to the city of Lignitz in western Poland. There the families rehabilitated an oil factory, and their economic situation improved quickly: Jews had once again proved their tenacity – their unbreakable will to survive. They had an accountant by the name of Moshe Altshuler-Eshel who eventually became treasurer of Hadassim.

Metuka: “We lived in a big apartment, and as more money came in we started eating like crazy. Meanwhile, I kept hearing that mother was still in Russia and kept expecting her to come back. It was really two years later that I realized she would never return to me, and I actually started calling Aunt Sara ‘mother’.

“Our building was solely occupied by Jews, and as I was the youngest I had no one to play with. One day Elisa Bar and her relatives moved in. She was as thin as a matchstick, with little blue eyes. She looked pallid green with malnutrition.

But it was great to have her with me, and we bonded immediately. We ended up taking the escape routes through Europe together on the way to Eretz Israel, where we grew up together in Hadassim.”

E. Wandering Through Uzbekistan

Moshe Frumin was born in 1940 in the city of Rovna, a northwestern Ukrainian city formerly of the Polish region of Wohlin. At the beginning of WWII, the city’s population numbered about 57,000, half of them Jews.

Moshe was one of our classmates. He was the only son of Israel and Yehudit. His mother was the head counselor for the village, and his Aunt Shoshanna was the counselor in our unit in the ninth grade. As our experiences in the village were often shared, Moshe and I grew very close.

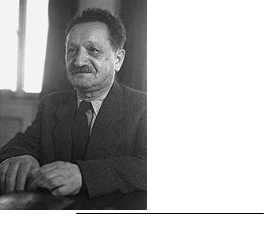

Moshe Frumin

Israel Frumin was one of the founders of the Gordonia8 youth movement and its leader in Poland. He made his living as a tax broker, but most of his time was spent in Zionist-pioneering activity. He’d been born into a very rich family of porcelain factory owners in the town of Kurtz; his grandfather was in the custom of sending every new model of the porcelain series to his daughter (Moshe’s aunt) in Israel, where she had immigrated as an early pioneer and settled in Rishon Le-Zion. Such was the family tradition.

The Frumin’s lived in a comfortable, two-story house. Throughout the years, they hosted several meetings of international Zionist leaders including Moshe Sharet, head of the political wing of the Jewish Agency (later the Israeli foreign and then prime minister) and Pinchas Lavon (head of Gordonia and subsequently a defense minister). Emissaries from Israel were frequent guests at their house. Prior to their marriage, Israel and Yehudit spent four years with a Godronia unit that was later destined to join the Kibbutz Mishmar Hasharon. In 1936, the leadership of Gordonia had arranged for their immigration and told them they were free to marry, but the visas never reached them – at the time, they were simply delayed because no replacement to head the Gordonia unit could be found. In the meantime, Moshe was born.

Several days after WWII erupted the city of Rovna was conquered by the Soviet Union. The German onslaught added thousands of refugees to the population, and as of June 1941 there were 30,000 Jews in the city. The Soviet authorities dismantled all Jewish institutions, including both schools and Zionist parties. Zionism moved underground at that point, and Israel Frumin was naturally one of its main activists.

After Germany declared war on the Soviets, Israel hired a coachman to drive his whole family east to Uzbekistan, where they would end up traveling from village to village for three years.

Moshe: “I was three years old. My father had taken ill, and I remember watching him on the carriage, waving goodbye. I never saw him after that, and nobody ever mentioned him again or told me what happened. My grandfather also died then. When my uncle abandoned us, the coachman ran away with our possessions.

Yehudit, the head counselor for the village,

“So my mother, grandmother, aunt and I were on our own. We went from one village to another, from door to door. Sometimes we were turned away, and sometimes we were shown extraordinary kindness – a glass of milk, a warm bath. The better portion of time was spent fighting off the unbearable hunger.”

In 1943 they reached the Moyen Kolkhoz in Uzbekistan, close to Kuvasai. The three women went out cotton picking, returning with bloodied hands. “They left me with Frieda, my grandmother. We were famished, of course. I remember actually crying out in hunger, and mother said, ‘When we come back you’ll have bread to eat, and you’ll eat as much as you want.’ But I went to sleep hungry that night, too.

“The Uzbeks, being Moslems, have dietary restrictions similar to those of Jews. One day I noticed a cow choking to death (rendering it untouchable by a Muslim) out in the field, and then I immediately heard our neighbor yelling at all thirteen of her kids, “Away! Get away from it, you dogs!” I was only three years old, but somehow I grasped what was going on and I immediately took my grandmother by the hand and led her toward the field, where we cut as much meat from the cow as we could carry back with us. Then we buried all the pieces under the clay floor, which functioned as our refrigerator, and this was enough to keep us alive for a while.

“The situation improved a great deal when mother found a real job, as a research assistant for an anti-communist agriculturalist exiled in Uzbekistan. There, on his orchards, I could have as much fruit as I desired.

“We returned to Poland when the war ended, and from there we took the escape routes all the way down to Eretz Israel.”

F. The Escape

In 1944, after the Ukraine was liberated by the Red Army, Jewish ex-resistance fighters formed a survivor center in Rovna for young Zionists who wanted to settle in Israel. These were joined by non-Zionists who were now shaken enough to view immigration as mandatory – living on what now amounted to an immense Jewish graveyard was no longer tenable. The kind of Soviet barbarity that drove their activities underground effectively ruled out any normal life for them in Eastern Europe. When they learned that Israeli agents were readying ships in Romania for mass immigration, the underground Zionists of Rovna moved quickly to join those efforts. The “Escape Movement” had begun.

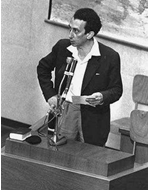

Abba Kovner

Similar developments took place in the Lithuanian capital of Vilna, without any connection to the Rovna group. Led by Abba Kov ner, Jewish partisan fighters left their forest dwellings and joined with members of the Ghetto resistance, and together they determined to gather as many survivors and escape to Israel. News of the Romanian efforts reached them soon enough, and they, too decided to head for the Black sea and sail to the Promised Land. Leaders of the Rovna and Vilna groups knew nothing of one another until they met in Romania. Unluckily, the KGB was ready for them there, and many were eventually tried on charges of Zioni sm and the smuggling of Jews. The “Escape” of Vilna and Rovna was blocked off.

Poland was liberated later that year. Many Jews who’d fled at the start of the war and found themselves under Soviet rule – like the families of Alex, Metuka and Elisa -- now returned to Poland. But it was Israel they wanted now, above all.

Most were concentrated in Lublin and Cracow. They began heading for Romania– by foot, by train or by car, almost all of them with false papers – as quickly as the war allowed. (When the war was over, many were able to travel and escape through Italy, Austria and Germany.) Illegal checkpoints were propping up faster than you could count them on Poland’s, Romanian and Czech borders.

All the while, none of these movements were coordinated either with the broad spectrum of European Zionist groups or the ongoing rescue efforts from the Zionist Organization in Israel.

The first organized framework for an overarching “escape” movement started with Abba Kovner – a partisan fighter, poet and member of the left-wing Hashomer Hatzair youth movement. On April 26, he inaugurated the Organization of Eastern European Jewish Survivors, but it was dismantled through Ben-Gurion’s influence. The wily politician was worried that his position would deteriorate without having control over such an organization. More importantly, however, Ben -Gurion intended to use the European refugee problem to his advantage, to bring about an Israeli state by exploiting world pity for ailing European Jews. It was a political move that required dislocated Eastern European Jews to remain dislocated, if only for the time being.

Once mass immigration efforts fell short in Romania, the wave quickly turned westward toward Italy, where units of the Jewish Brigade of the British Army were already stationed. The soldiers there established a central organization for the incoming refugees, led by a coalition of various Zionist parties. By August 1945, 15,000 Jews had arrived in Italy. But immigration into Israel was still technically illegal and strongly curtailed, and a practical decision was made to direct the flow of refugees back into Germany.

After the war, what had previously been a more or less spontaneous “escape” movement was consolidated into one enormous and brazenly illegal organization, whose bold aim would now be to move as many Eastern European Jews westward and thence to Israel. The new organization was spearheaded by Shaul Avigur. The first Israeli emissaries arrived in Europe in September 1945, helping to direct refugees through several points in the Polish-Slovakian Mountains and through higher Silesia to the Nachod district in Bohemia, or through Stettin to Berlin. Those escaping through Czechoslovakia had to move through Prague into Bavaria, or else through Bratislava to Vienna and thence to Salzburg. Though the Soviets had tightened their grip on Eastern Europe, they usually let these movements proceed apace, sometimes even abetting them. In other cases, however, they arrested refugees and hunted their organizers, condemning them to years of torture and even death in the Gulag archipelago. So it might have been capricious, but the standard Soviet attitude was: see no evil, hear no evil.

The British response to these developments, of course, was decidedly hostile. Nevertheless, American forces eventually facilitated such rescue efforts. Whether it was out of concern for public opinion, or whether it was the fact that American soldiers weren’t going to fire at helpless refugees, the result was the same.

The Jewish Brigade joined in this endeavor. Prominent among them was one Moshe Zeiri, who directed an orphanage in Slavino, Italy. He subsequently became a cultural coordinator at Hadassim. Many Holocaust survivors led the effort as well, including one of our future teachers, Zeev Alon, as well as Masha and Eizik Zarivetch and Yizhak Lerner -- all three destined to work at Hadassim.

In 1945, Jews in Poland began to flee in panicked waves when the blood libel reared its ugly head throughout the countryside, stirring random murders of Jewish refugees. Ten thousand Jewish Poles now penetrated en masse into Germany, including those who had originally had every intention of resettling in their native cities. These pogroms were more than enough to clarify, for those who needed it, that anti –Semitism would not end with the fall of Nazi Germany9.

G. The Children’s Journey in Europe

The Children’s Journey in Europe

Israeli emissaries of the “Escape” Organization arrived in Poland in 1946. There, Holocaust survivors were made to understand that British prohibitions on settlement in Palestine made exceptions for children -- especially orphans. The emissaries proposed to take as many children as possible with them to Israel, where they would be brought up in the finest educational establishments in the country. Relatives were promised that these children, who had miraculously survived the Holocaust, would arrive safe and sound in Israel within two weeks. That was the beginning of the Israeli journeys of Shevach, Metuka, Alex, Elisa and Ephraim.

But these promises turned out to be unfounded, and may even have been a conscious deception. Who authorized them? Was it actual policy, or was it nothing more than an improvisation on the part of a sabra who assumed it would somehow “work out” in the end, come what may?

Documents exposed in recent years show that the World Zionist Organization resisted any immigration initiatives outside of its designated purview.10 Its formal policy was one of “selection” – the selection and salvation of people it specifically determined as fit and skilled to serve a Jewish State. That meant the explicit abandonment of those it deemed “unfit”. “Such selection is directed toward those young European men and women who are trained for productive ends. …It would be giving the most dangerous ammunition to Zion’s enemies to conspire in flooding Eretz Israel with the elderly or undesirable…”11

With the extermination of Jews at its peak – and there were those in Eretz Israel who knew the full extent of it – with only a decimal of Warsaw’s Jews still alive after the second liquidation of the Ghetto, Dr. Yitzhak Grinboym (leader of the Polish Zionist movement between the wars and subsequently chief minister of internal affairs in Israel) was faced with a dilemma: Jewish lives or Jewish settlement. He opted for settlement.

The Children’s Journey in Europe

He opted not to save lives.

The following is the relevant protocol of the World Zionist Organization’s directorate:

Yizhak Grinboym: “When I was asked [whether money should be requested] from Keren Hayesod 12 [to finance] the rescue of Diaspora Jews, I said no. And I’ll say no again! I’ve been disputing exactly this point for months now, with someone who knows what he’s talking about! His name is Rabbi Itche Meir Levine, and he always tells me the following: go and ask Keren Haysod’s for money… ‘Couldn’t you suspend the work on Eretz Israel at a time like this, when Jews are being massacred in the hundreds of thousands, in the millions? Spend the money on them – no new settlements!…’ No, on the contrary, it must be said here today that Zionism stands above everything else.”

Sofisky: “But surely even from a Zionist point of view we are obliged to steer part of the budget toward any possible rescue efforts…”

Yosef Sprinzak [subsequently the first speaker of the Knesset]: “My handiwork is drowning in the sea13 and here you talk to me about a Zionist program?”

Grinboym: “They’ll call me an anti-Semite, [they’ll say] I don’t want to save the

Diaspora…But I will never demand that from the organization’s budget, I won’t demand it from what precious little we have. No, I won’t ask for a sum of 300,000 [to save the European Jews]. I will never demand that. And I think whoever demands it is committing an anti- Zionist act14.”

Yizhak Grinboym

Some of the emissaries to the “escape” operation sent by the Zionist Organization were unimpressed with the caliber of refugees they encountered, so they acted to prevent or at least delay their immigration. When they returned from their duties in Poland early in 1946, some of them met with Ben-Gurion and told him outright that it would be a disaster if all these survivors were allowed to immigrate. “To have all this filth already roaming the earth is bad enough…but you’ll have them here, in Eretz Israel?!”15

This kind of sentiment toward Holocaust survivors actually resonated widely with the Zionist elite in Israel. To quote David Shlatiel, a Hagana commander and a relative of Ben-Gurion: “That somebody was in a [concentration] camp can’t be reason enough to have him in Eretz Israel. Those who survived did so because they were egoistic and cared primarily for themselves.”16 Shaltiel warned against these “egoistic” people who would endanger the project of settlement.

Yosef Sprinzak

The “escape” activists who drew a quarter-million refugees into Western Europe put the Allied command in an impossible situation. Had Britain opened Israel’s gates to a hundred-thousand of these refugees, they might well have placated Jewish demands without necessarily risking Arab revolt. Israel’s Arabs were frightened and rather off balance when the Germans lost. As it turned out, however, an inflexible British policy combined with American sympathy for the Zionist cause spurred the rise of Jewish sovereignty in Israel. In that context, the children of the “escape” operation and the myriad camps of uprooted and suffering Jews all served as powerful ammunition in Ben-Gurion’s hands.

Metuka, Alex and Elisa were supposed to take several days to arrive in Israel. In the end, their journey lasted about two years. At the same time, on the very same roads, the Weiss and Frumin families -- together with a quarter-million Jews – were poring into European escape routes. These children, these hundreds of thousands of human flesh and misery, would serve as the diplomatic ammunition which Ben-Gurion would wield in creating a Jewish state.

Alex: “My uncle, my adopted father, spent a great deal of money for our official immigration. It turned out that the emissary’s commitment was unreliable at best. One thing is certain: when they made their commitment to us they did so without authority, and told us things that weren’t true. It’s been sixty years since then, and it’s still unclear to me even now if it was simple fraud from the beginning, plain misfortune or else wishful thinking on both sides.

Ultimately, Metuka, Alex and Elisa were herded onto a train with a hundred-fifty other orphans and driven to the Polish-Czech border, but since they lacked passports, and since all the states had long sealed their borders subsequent to the war, the children had to wander around disguised as gypsies to avoid scrutiny. They waited till nightfall to cross the border and found an unguarded section.

Metuka: “We traveled in military trucks left over from the war, and many were clearly unreliable. We infiltrated borders in secret, always after excruciatingly tiring journeys. Disease was rampant, especially severe ear infections. I can remember Elisa walking in front of me through the forests, like a human skeleton, barely conscious from all the pain and dripping with pus from infections. That was how we spent the European winter. One day we took shelter in an abandoned military camp, and what did we see there? Another orphan’s group -- wandering around Europe just like us. Another camp we passed through in Esau, near Munich, was directed by a future teacher of ours in Hadassim, Zeev Alon.

“We were finally able to rest for a relatively long stretch when we settled in the Furten camp. Our counselor there was Masha Zarivetch, and her husband, Eizik was one of the directors. And it was there that Ephraim Gat joined us. We awoke every morning to a loud alarm; I used to lunge out of my bed in terror at the first sound of it. To this day

I keep wandering how our counselors could have been so inconsiderate in this respect. They could easily have used a gentler means to wake us up, given our war traumas.

“It was there that we were first taught a little bit of Hebrew and some math. We would get packages every so often, with chocolate and toothpaste, and soap. Of course, we exchanged the soap and toothpaste with the Germans in return for apples, plumes and pears. “

Furten

Elisa: “In Furten we stayed in these giant military halls. Sometimes we’d go into the forest to pick blueberries. I got pretty sick on one of those trips, and they took me to a hospital in Munich. I was left there by myself, and became very frightened all of a sudden to be alone around all those Germans. I felt like I’d been abandoned there forever.”

Around the same time, Alex and Metuka’s relatives found their way to a refugee camp in Austria. It was there that their aunt Sara learned that, far from being in Israel, her niece and nephew were still out in the harsh cold of European winter. She realized that her “escape” agent had made a fool out of her, and asked her brother Maneck (who had just arrived back from Russia) to bring them back. But Maneck happened to arrive in Furten the very same day that travel certificates arrived for the first group of children (and their counselor) destined for Hadassim.

Metuka was supposed to be among those first eight children, but Maneck had no way of knowing that by the time he dragged her off with him back to Germany. Alex stayed in Furten and was eventually slated to join the famous “Exodus” ship to Israel.

The group of eight left with Masha Zarivetz the very next day. Their first stop was in a sanatorium on the Warburg estate in Belkanza (near Hamburg) devoted to prospective child-immigrants to Israel.

Elisa: “What kind of things would any clinician or psychologist look for in such an institution? He might have asked whether there were warm beds, whether the counselors showed affection – how often the kids were hugged, for example -- whether the environment allowed for laughter and the freedom to say ‘no!’ He might have asked whether the kids were finally allowed to cry and pour out their emotions after what they’d seen, what kind of emotions were treated as normal.

“Any health professional by today’s standards would have noted the presence of these crucial factors at Belkanza. Most of us, aged five to nine, had managed to remain intact through the war, but we still needed something to help us move on. They projected onto us their own strange notions of what a ‘child’ and ‘childhood’ are supposed to be, and there was still a pure instinct to dim our emotions in order to go through a kind of intermediate, cleansing stage. We knew deep down that we would have to leave this horrible period of our lives behind, even by repressing and running away from it. So we basked in the light, we lived in the moment. The past would come to be seen as an era of darkness, much too painful to delve into even if it could shed some light on our own demons. In many ways this remains the case. How does one close Pandora’s Box once it’s opened?

“There were other ways that Belkanza gave us a bridge to a real childhood. We were taught Hebrew for the first time. They used an introductory booklet that showed all the letters. The process was almost hypnotic for me; the sounds of the language were completely new, with strange symbols indicating vowel sounds (nikud). None of it matched the language and sounds that we knew, yet this was the first alphabet we’d really seen. ‘What about the sounds I already know?’ I thought to myself. ‘Does Polish have symbols like these?’ We didn’t ask those questions, so naturally they weren’t answered. Then, some of it was just hilarious. ‘Why is the picture of the horse shown twice, only the second time it’s called a ‘donkey’?’ Yet we were finally allowed to be children; we were being taught in a classroom, we were looking at pictures, we were at the center of attention. We were part of the human race again.

“The Belkanza team could probably have taught beyond this rudimentary level, and there were indeed prizes handed out to those who accelerated their studies. I don’t remember any harsh discipline or punishments, really. I do remember the gifts, of course– the jump-rope, the little wooden dog that jerked every which way at the push of a button. Those were all the possessions I had, for a while. The whole group of us wore out that jump-rope completely. Then, finally, we were shipped off to France, and from there to Israel.”17

H. Camp 55 in Cyprus

“Moshe Frumin, his mother and grandmother had crossed the Polish border into Czechoslovakia and found their way to Italy through Germany and Austria. On their arrival at the Milan train station, the seven year old Moshe suddenly found himself alone with his grandmother. His mom had momentarily disappeared among the crowds. Grandma Frieda was having more and more difficulty even standing up, having strained her leg along the journey. “We sat against a pole for a few minutes, and then suddenly I wasn’t feeling very well. There was a small medical office nearby with a children’s wing. There were some toys laying around, the first I’d ever seen. A doctor came in to see me. When he left, I turned to grandma and said, ‘Let’s get out of here. We’ll never find mother if they hospitalize me.’ So we came back to the train station, and suddenly I saw two young men walking close to us wearing green ties – the Gordonia emblem. I immediately grabbed one of them by the hand and didn’t let go; I felt that my whole family’s destiny was on the line. Though I was very young, I realized it wasn’t right that our journey should stop in liberated Italy. I told him what we’d been through, and he told me they’d actually been looking for us the whole time we were in the hospital. He said to wait there for someone to pick us up, and eventually a man wearing a long black coat arrived. He looked around to check that we were along, and then handed me a stack of Italian liras and told me to take the train to the naval school of the ‘Schola Kadrona.’

Moshe Frumin

“We arrived at the naval school, which was located inside a giant three-story building, and were immediately shown to our beds. I ran down to the basement to bring some mattresses, grappling with all the other refugees for an extra bed for mother when she would join us. The director of the school had promised that my mom was on her way, but she never showed up. After about a week we were finally told that she was being held in jail cell on Via Unone St, and when we went there the police wouldn’t let us near her. I could only see her from a distance, looking at us from behind the bars.”

At this point in the interview, Frumin’s voice was shaking slightly, and his eyes filled with tears. As an artist, he has used his craft to overcome his separation from his mother. The Pieta motif runs through his “Mother and Child” statues.

“Apparently she’d been arrested at a border crossing-station. So we went back to the school, and soon afterwards mother was released and was able to join us, along with aunt Shoshanna and her husband Yitzhak.”

From Milan we traveled to Bari, where we stepped onto a small fishing boat and sailed into the heart of the summer sea and boarded a ship headed for Israel via Sicily. We arrived at the coast of Haifa on July 7th, 1945. Seven large British ships surrounded the port entrance, and up above we could see three airplanes circling. It was as if Holocaust survivors were suddenly the most terrifying enemies of the British Empire. We were guided down toward the pier, where they registered all the passengers and stripped us of all our possessions. I tried in vain to hold on to my mandolin, a gift from my uncle Yitzhak, as it had always symbolized freedom for me. They practically tore it out of my hands. It was an important moment for me, because I realized then that Germany’s enemies weren’t necessarily our allies. It wasn’t long before they packed us onto a warship and sent us to Cyprus”

Sitting in Frumin’s studio near Akká, we gazed admiringly at his various sculptures. One of them in particular caught our eye, a magnificent rendering of King David’s lyre. The story was that young David’s lyre had tamed the savage breast of Saul. Moshe had likewise cheated death more than once, and thus the lyre topic was clearly one more articulation of his own narrative -- it was his way of internalizing his own childhood struggles, of reclaiming the mandolin that the British had taken from him.

“In Cyprus, the British placed us in an Indian tent in a makeshift refugee camp, referred to simply as camp 55. The inhabitants were organized on ideological lines, so we were thrown in with the “Gordonia” group. When Moroccan Jews started arriving, quarrels between them and the Poles became common. It was a reflection of times to come, of Israel’s future social and ethnic divisions”

There was a couple at the camp, Shoshanna and Yitzhak Lerner. Shoshanna had just given birth to a daughter, Lea, and the British allowed them entry to Israel. They came to live in Hadassim at Rachel’s invitation – Yitzhak was her cousin – and he became an official driver for the school.

“We only immigrated after statehood was declared. Initially we were sent to a transit camp 89, near Pardes Hanna, but Yitzhak arrived to take us to Hadassim the very next day. I was placed in the third grade together with Yakir Laufer and Moshe Lieberman, and we were later joined by Metuka (who we called “the old lady”). Our primary teacher was Bluma Katabursky, Rachel Shapirah’s sister. Mother was eventually accepted there as a counselor.”

I. Aliyah Gimel