Book.

The Discus Thrower and his Dream Factory

Chapter 2. My Family, my Childhood and my School

The Village Hadassim

The Village Hadassim

My father, Moshe, was born in Poland in December, 1904. His parents were older and had thought their childbearing years had ended long before his birth. He was essentially raised as an only child since most of his siblings had either died or moved away. Based on his subsequent behavior towards me and my mother, I believe he must have both seen and experienced physical and emotional abuse.

My Father in the British Army and latter in Jerusalem

M

My My father was extremely intelligent and excelled in all academic subjects as well as in his artistic skills, mainly in drawing. However, this exceptional intelligence was somewhat a disadvantage for him in his youth. Because of his academic prowess, he was sent to the Gentile high school, called Gymnasium. He was accosted and beaten regularly by the Gentile kids because he was Jewish and then received the same treatment from the Jewish kids for attending a Gentile school.

Finally, in 1922, my father was sent to the Holy Land – Israel. At that time, the country was ruled under the British mandate and was called “Palestine”. Ships arrived at the port of Jaffa, at that time, which was one of the oldest ports in the ancient world. While my father was trying to cover the relatively short distance to Tel Aviv from Jaffa, he was set upon by thieves who beat him and stole all of his possessions.

Life improved for him and shortly thereafter, he had a job as the manager of a hotel in Tel Aviv. Eventually, he became head of the customs at the Jaffa port, perhaps because of his fluency in seven languages including English. This was during the period after World War I when the British continued to rule “Palestine”. The Jaffa port turned out to be an excellent posting for someone whom I later learned was charged with stocking ammunitions for the resistance. My sullen, angry, removed father was part of the Stern Gang, those who were violently opposed to the ruling British since this group, as did others, had aspirations that this land would again be the Jewish homeland.

It was a shock for me to discover this detail about my father. I actually learned quite by accident that he was such a nationalistic fighter. I was with him at the port one day when I was still a young child and, with my natural curiosity, began opening drawers, doors, and closets in search of a treasure or a toy. I found some amazing oblong rigid pineapples and assumed they must be toys of some kind. Of course, my father nearly had a heart attack when I showed him my discovery which was actually a hand grenade! He could have been hanged by the British for smuggling these weapons. This revelation about my father was somewhat surprising to me since I had never thought of my father as being rebellious at all. But I did know that he was violent.

We lived in a small apartment in Tel Aviv and we lived simply as people in Israel did then. We had a small kitchen, a tiny living room, and a small balcony with a few flowers. My mother worked full time as a secretary to the mayor of Tel Aviv. She seemed to infuriate my father for reasons I could not understand, as a young boy would not understand most adult issues. He worked all week at the Customs Office but when he did come home or stayed home on a weekend day, our exchanges were usually accompanied by abusive words or brutal smacks to my face or body.

My Mother and with my Father

This anger confused and puzzled me. I knew that my father loved me. I never doubted that concept. But, for some unfathomable reason, he was unable to express his love in a way that I could recognize. The same held true for my mother. Undoubtedly he loved her, but was not able to demonstrate this affection appropriately. Maybe he was inhibited, overwhelmed by family life, or merely lacked any comprehension of what he was supposed to do in this situation.

I knew my father had grown up surrounded by education. His father was a Rabbi and, in addition to my father’s talent for languages, he was also reputed to be a gifted painter. I heard people throughout the neighborhood talk about his talent. After Israel was declared a State, my father had a new job as an accountant. But his behavior was the same as it had been when he had worked for the Customs. I will never know what so bedeviled my father because he never spoke about such things. Israel at that time was full of people who could only lash out. There were those, of course, who turned their sadness into ferocious wit or goodness. But many people were marked by unspeakable memories of their own or of those they loved. Silent hurt was in the air. There is a theory that what you saw, heard, and experienced in your own childhood is what you repeat when you become an adult. In our more modern era, I think there would have been groups or government agencies which would have intervened to help my family situation. Anger management, marriage counseling, and child rearing assistance were all areas in which my family needed help. Sadly, for my mother and I, as well as my lost and confused father, such help did not exist at that time.

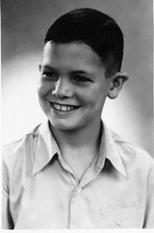

Me, at very young age

Me, at very young age

My Father and I at a young age

My Father and I at a young age

My mother was a gentle, pretty, kind woman who loved me. Many times I witnessed my father hitting or shouting at her. She, it turned out, found solace elsewhere. Eventually, she had an affair with her boss, the mayor of Tel Aviv, and apparently she was also involved with a prominent Israeli engineer as well. I know this now. Then all I knew was my father would point to her and say to me, “See that whore?”

My Mother and me at the Tel Aviv shore

Eventually, my father divorced her which probably was not that upsetting to either of us. Unfortunately, at that time in Israeli society, divorce was considered a terrible act. For example, many parents told their children, my friends until then, not to play with me because my parents were divorced. What a dreadful situation for a young child to have to experience. First, violence at home, followed by confusion after the divorce, and then to have no friends for talking and playing.

My Father

My Father

My Father and Mother

My Father and Mother

My mother and I, who had now reached about 10 years of age, lived together alone. Usually, I was sent outside on an important errand when my mother’s male friends would drop by for a visit. On one occasion, instead of leaving, I hid in a closest when she was with one of these men and watched what they were doing. This was my first vision of sex, and, although I did not understand what was transpiring, I knew it was something she was not supposed to do. Eventually, my mother became pregnant. I came to understand that both of these men were already married and neither was going to take responsibility for the baby. My mother gave birth to a daughter, Nitza. Many years later, I learned that my father had gone to the hospital and put his name on the birth certificate, despite the fact that he was not the biological father, so that this innocent little girl would not be born without a name.

Still, my father wanted nothing to do with my mother. Now it was my mother, the baby, and me living together. Imagine, at the age of ten, I was the man of the house.

Nitza in the Israeli Military

Life went on with my mother tending to the baby and me. One day an ambulance came to the street and, to a young boy, this was very exciting. It was thrilling until two uniformed men entered our apartment and forcibly removed my mother. My mother screamed and resisted this attack but she was much too small and weak to fight two strong men. I stood at the door watching and crying, literally left holding the baby. Some of the neighbors helped me with Nitza and with food, but I did not understand what had happened nor why. All that I knew was that my mother had been taken away and Nitza and I were alone. I can’t recall how many days and nights we spent alone, however, I do remember how frighten I was, especially at night. I did my best to conceal my fear from my sister, and to this day, I’m not sure if she knew of the perils we faced on a daily basis.

![File0006[1].jpg](https://cdn.arielnet.com/__resources_/books/gba-wri-01002/chp-02_files/image019.jpg)

Me at 10 and 11 Years Old

No one would tell me anything. Finally, my father came and took me to his apartment which was in another part of Tel Aviv. .over and over again “Where is my mother?” When the door opened I was stunned. Usually when a neighbor would come by with food, or simply to look in on us, there would be a knock on the door. The only thing I can remember is asking him,

Earlier that same day two women appeared at the apartment and took my little sister away with them only offering that she would be kept safe. At least they knocked on the door minimizing my trauma. I tried to stop them, but a small boy was no match for two grown women.

“She is in an asylum,” he finally answered. I didn’t know what that meant, but at least he offered an answer.

“Where is Nitza?” I asked.

“She is in an orphanage.” Okay, now I had some answers! I neither knew what an asylum was, nor, an orphanage.

Everything was so confusing to me at the time. I was in shock but had no information to consider or question. I had no idea what to ask and just retreated into my normal shell of quiet and confusion. My father told me that things would be a little different for a while and that I would live with him. No one would tell what was happening to my sister. I learned many years later, that Nitza was finally adopted from the orphanage when she was about 6 years old. She was adopted by the engineer, who was most probably her biological father, and his wife.

I asked about where my mother was until finally my father told me the name and location of the mental institution where she had been taken. After considerable pleading with my father he finally gave the fare to catch a bus. I took the bus by myself to see her. I followed the nurse to where my mother was sitting. I wanted to understand what was going on. How could she be taken away from me like this? I was taken to a large room and there was my mother and she was very happy to see me. She held my hand and asked me about school. I was very confused about why she was there and what was happening. Her hair was very messy and she had trouble concentrating. She would ask me the same questions repeatedly. The nurse announced to the whole room that visiting hours were over and we all had to leave. The nurse asked me to accompany her to her office, probably because I was crying.

The nurse was very nice and gentle with me. Clearly, she recognized that I was a vulnerable young boy, scared and with no idea what was happening and what I should do. She told that my mother was quite ill and might be in the hospital for a long time. She explained that every human being is like a glass of water. Sometimes, the glass is too full and the water spills over the top edge. When this happens, the people have to go to the hospital like my mother. The nurse tenderly held my hand and told me that I needed to focus on school and growing up to be a good boy. I should not worry and dwell on my mother and her illness. Otherwise, this obsession could make me sick as well. The nurse assured me that the hospital would take very good care of my mother so I need not worry. I left the hospital not knowing any more than when I had arrived, as I remember, about my mother’s condition. At least I was able to see her and hold her hand for a few short minutes. My tears were many but short lived as the winds of change continued in my life.

Now I lived alone with my father. I had always been a curious child and that created lots of problems with broken things. My mother had chalked up these “accidents” to the rambunctiousness of boys and ignored most of my behavior. My father, on the other hand, was very proper and neat. He had no experience with a boy who investigated the insides of a watch and then could not put it back together. Also, he did not like the messiness of collecting turtles, silk worms, and lizards. In retrospect, I cannot imagine the difficulty my father must have experienced as his life and mine continued to spiral out of control. His wife was gone and his son was difficult. It was not until fifty years later that I learned how deeply he had loved both of us but had been incapable of expressing that love. At that time, however, he was working full time while I was wreaking havoc whenever and wherever I could.

Not all of my activities were destructive, however. I was already entrepreneurial, delivering roses for money, although I usually kept one rose for myself and then sold it at half price! Naturally, being busy with my extracurricular activities, and the sadness and emotions, that were began taking its toll, I began failing my exams. There were no teachers at my elementary school that recognized my anguish and family difficulties. So if I were day dreaming instead of listening, the teacher would insult and ridicule my incorrect response to her question. There were never any kind words, extra help after class, or sympathetic understanding. I began to skip school altogether, preferring to build sand forts at the beach. This truancy led to missed classes and failed tests. Therefore, I was not passed from fourth grade to fifth and was forced to repeat the fourth grade class. In Israel, where academics are prized above everything, this was unforgivable. I was classified as a truant, a loser, possibly as crazy as my mother. None of the parents in the neighborhood would let their children play or talk with me. My father was now even more frustrated with me and told everyone, in front of me, that I was “lo utsloch” which in Hebrew meant that I was unsuccessful now and would continue to fail in the future unless I changed my behavior. He could not cope and was at a complete loss about what to do. He could not work full time and care for a young boy.

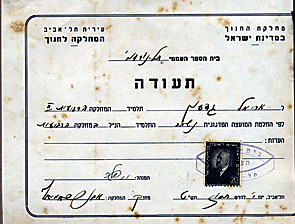

Grade Repeat certificate (Or for a child in Israel at the time: A Death Certificate)th4

Sadly, if he had looked more closely, he might have seen the burgeoning signs of a future. I loved to go to the arcades at the Tel Aviv beach and play with the mechanical machines. I took apart radios and watches and spent many pleasant hours fixing my round of endless bikes. In other words, I was already fascinated with mechanical issues.

Someone said to him, “Why not send Gideon to Hadassim?” Hadassim was a small, rural residential school a short distance from Tel Aviv. He visited the school, without my knowledge, and they were quite willing and eager to accept me. From the moment I arrived at Hadassim, a scared and traumatized child, my world became brighter and my life blossomed into a garden of growth, happiness, and dreams.I wasn’t all that enamored with the thought of ‘going away to school’ as would be the expected response of most young children. My father never tried to sell me on the idea, it more of a matter of fact – you are going son, it is what is best for you. At this age there was little I could say or do, so off I went.

Early life in Hadassim

Early life in Hadassim

The WIZO-Hadassim School village, where I was sent, was a small collection of buildings near the town of Netanya just north of Tel Aviv. It had been specifically created to educate traumatized children. The school’s main mission, as set out by the Hadassah-WIZO Canada, who financed the school in 1947 to the tune of what is now one million dollars, was to house, restore, and educate the Holocaust orphans. These children had lived their first ten years in basements, boxes, windowless hiding places, in constant fear, hunger, and denigration. More than a few of them had actually witnessed their parents being murdered and a few had been the victims of medical experiments.

These Holocaust children were gathered at a transitional camp for war-orphans on the Warburg estate in Balkanza, which was near Hamburg, Germany. From there, they initially travelled to Paris and then on to Marseilles, France. In Marseilles, they boarded the ship “Providence” which sailed to what was then Palestine. After a short stay in WIZO-Achuzat Yeladim on Mt Carmel in Haifa, Israel’s main sea port, they boarded a train and arrived at Hadassim in 1947. These were Hadassim’s first students and were mainly fourth, fifth, and six grade students.

Before these war-orphans arrived, A WIZO general council in Jerusalem had decided these children should not be segregated from normal society and so other “traumatized” children were to be allowed to attend the school. All of these “traumatized” kids were from families with problems. The problems could be divorce, as in my case, or where one of the parents had died and the surviving parent was unable to work and also care for the child. In addition, to balance the learning and emotional experiences for everyone, some children of diplomats and those from more financially privileged families were matriculated amongst the general population of the school.

My own journey to Hadassim was from the second group, “the traumatized”. My parents were divorced and my father experienced numerous difficulties trying to care for me and having to work a full time job. It was his decision to send me to Hadassim since he believed that I would be cared for and educated in a better environment than he could provide for me living alone with him in Tel Aviv.

Hadassim was run as a commune. Everyone, students and teachers, participated in every activity. We had tasks in the school to keep it clean. We were responsible for maintaining the cleanliness of our door dorm rooms. We helped with the food production and farming jobs. In addition, we had to study and complete our lessons. There were few amenities with hot water being one of the missing ones. Most importantly, we had each other and the belief that we could become anything or anyone we wanted to be. There was never a hint or suggestion that we were damaged or deficient in any way. We were raised with the diametrically opposite concept – that we were wonderful people in a beautiful, loving world.

Dancing at the Beach and at Home

The philosophy of the school was each child would be nurtured to develop his or her own particular gifts, be they in the humanities, science, sports, or art. “Dialogue” would be the main way of teaching. There was dialogue with each other, with the teachers, and with God.

Arriving at Hadassim

To inspire the students and try to alleviate the pain that so many had suffered, nearly every week some distinguished person would come to Hadassim. Many of the world’s finest artists appeared at Hadassim including the violinists, Yasha Heifetz and Yehudi Menuhin, the choreographer Martha Graham and her troupe, the harmonica player Larry Adler, and the comedian Danny Kaye. The students met Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of Franklin Roosevelt who had been the President of the United States and with the scientist and current President of Israel, Professor Chaim Weizmann. The best of Israel’s directors staged plays at Hadassim and the most talented musicians taught music there.

More about the Village of Hadassim in Appendix 1.

This inspiration must have been successful in its goal. For example, the Hadassim dancers became one of the most accomplished dance troupes in Israel during the 1950’s. Students from Hadassim achieved Israeli records in athletics and represented Israel at two Olympics. It should be noted that although Hadassim students fought in all of Israel’s wars, none tended to military careers and there were no generals among us. Dialogic concepts inspired by Martin Buber, who was a secular Jew and believed in discussion, not war, and led us towards a humanistic, non-militaristic way of life.

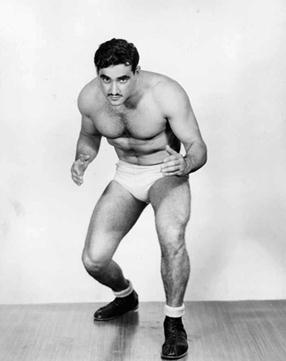

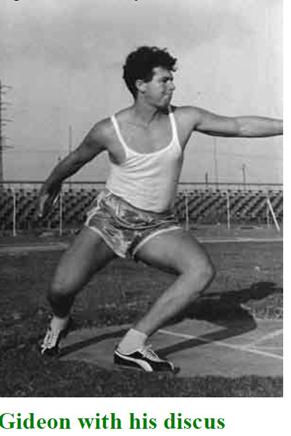

We all pursued what interested us individually. Some of us danced, others wrote stories or poems, many were interested in politics or scientific pursuits. Even before I had gone to Hadassim I was fascinated with exercise, physical strength, and the many ways I could enhance my muscular prowess. Maybe it was nascent talent or perhaps I was inspired to emulate the abilities and accomplishments I saw and read about in athletics. One of my heroes was Rafael Halperin, who was Mr. Israel and a world champion in professional wrestling.

In Hadassim I continued to be interested in exercise. One day, an American kid, Zvi, gave me a new exercise spring device. Zvi had been sent to Hadassim by his parents who lived in New York. His parents had gotten a divorce and sent their son to the dorm school in Israel to learn to be a good Jewish boy. Zvi was a small, skinny boy who was quiet and relatively passive. It was unclear whether this was due to the language barrier or just his natural character. One particular day, we were all exercising by lifting a weight consisting of the two wheels still attached to an axel that had originated been part of an old freight train. A big Israeli boy, Kombor, pushed Zvi out of his way. This was a real David and Goliath moment! The big bully taunting the little kid. All of sudden, Zvi had had enough of the bully’s aggression. He lashed out with arms and legs flying in a whirlwind of motion. Because Zvi had always been small, his parents had enrolled him in judo, karate, boxing, kick boxing, and self-defense classes in the United States. In what seem like mere seconds, the bully was down and out! We, the on lookers, were more than stunned to have seen this transformation and unqualified victory of small defeating large. Then Zvi calmly extended his hand to help the wounded Kombor to his feet. These two unlikely adversaries became best friends thereafter.

The new exercise gadget was a big event at Hadassim. Zvi showed me, to my amusement, that you could stretch the springs into different shapes to be able to exercise different muscle groups. The exercise device consisted of 5 springs which could be attached or detached, depending on the amount of resistance you wanted to create. You could hold both handles in your hands and stretch the device or connect one end to the towel hanger and pull against it. Because the handles and springs could be arranged for any number of exercises, I felt that this device had an advantage over the barbell weights I had created for myself using fruit containers filled with cement. I had connected the cement-filled containers with a pipe to create a “bar” for my “bells.” But I noticed with this new spring exercise device my effort necessitate much greater effort at the end of the motion rather than at the beginning. This change of resistance throughout the range of movement resulted in more effective results of my training. In other words, this spring device forced my muscles to work in the middle and at the end of the movement as well as at the beginning. It was much more difficult to pull at the end, but produced much more beneficial results.

The Spring Exercise device

The Spring Exercise device

I could not read the English manual, but Zvi helped me. I was fascinated by the story of a Mr. Miller who described how unathletic he had been in his youth and how well developed he became using the exercises described in this book. This book was much more interesting to me than the school books I was supposed to read. I followed each exercise and supplemented it with the exercises I devised for myself. I would do these exercises every day, 7 days a week to the amazement of my classmates and some of my teachers.

I used my set of home-made dumbbells and barbells during the afternoons after school and before going to kibbutz work. I noticed that when I did various exercises, such as the Bench Press lying on a bench, that the weight became lighter toward the end of the movement, unlike the spring device where the resistance increased toward the end. This was my first biomechanical intuition although I could not have explained it in those days. One day, I had an inspiration. I decided to modify the barbell in a way to achieve the same effect that I experience with the spring device. I hung chains, made out of heavy metal, at the end of the barbell so that part of the chain would drag on the ground while I started the movements. As I pressed the dumb bell up, the action pulled more and more of the chain off of the ground and, in this way, made the weight heavier toward the end of the movement. This created a variable resistance exercise. I was thrilled by this invention. I could feel how much harder I had to lift and discovered many new muscles that were sore from the effort. The most amazing thing for me was the increase in the size of my muscles with my newly “invented” device.

Getting stronger with training and time.

A week before my thirteenth birthday, the lucky kids in Hadassim went home to their parents to enjoy the Pesach, or Passover, vacation. Although this is one of the most important Jewish holidays on the calendar, I had to stay in Hadassim with some of the other children who also had no place to go.

The Pesach vacation was 3 weeks long. To keep us busy and our minds off our loneliness, we had a busy daily schedule which consisted of 8 hours of farm work on the Kibbutz. My duty was to cultivate the hard, dry soil of Hadassim for the next crops of corn and wheat. I would drive the Farmel tractor that I loved so much. I may have been lonely, but I loved to drive that tractor.

On this day, April 27, 1952, I was suddenly summoned to come to the main office for a visitor. I left the tractor with its engine running and walked up the pathway towards the dining hall.

Suddenly, I saw my father standing there with Rachel Shapira, the school Principal. Granted time fades memories; however, from a very early age there have been specific events in my life that that have been burned into my memory much like a tattoo stains the skin. This was one of those many moments in my life. It had been a long time since I had seen my father and was certainly surprised by his presence. I remember vividly looking up into his eyes and noticed how they sparkled in the brightness of the day. I thought, at the time, that I had never seen anything like that. Now as I remember the event I know what made his eyes sparkle; it was my father’s tears welling up in his eyes. There is so much that a ten year old boy doesn’t understand. “Shalom Abba, what are you doing here?” I asked incredulously.

He leaned towards me and whispered, “Do you know what day it is today?” His voice was unusually soft as I remember it.

“It’s my birthday,” I answered.

“Yes,” he said slowly. “It’s your Bar Mitzvah today - did you remember that?”

Well, of course I remembered that. What kid would not? I was a little surprised that he remembered and more so that he made the trip to see me.

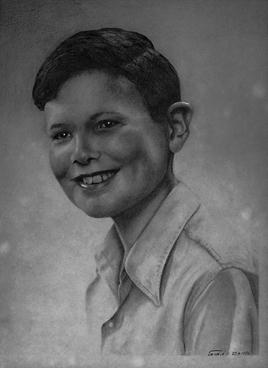

“I brought you a present,” my father said, handing me a small box wrapped with old newspaper. At that time in Israel, there was no fancy colored paper that we have in our modern times. I could not open it fast enough. I ripped the paper off and found a charcoal drawing of myself which had been painstakingly sketched by my father.

“Is this my present?” I asked, trying desperately to hide my disappointment.

“Yes, Gideon, do you know how difficult it was for me to do this? It took me many hours to draw it. I hope you like it.”

“Thank you, Father,” I replied, thinking, how stupid it was to give me such a present. Most kids would get much better presents and some money. I wished he had given me one “Lira”, which was an Israeli Dollar, instead. I could do so much more with one dollar than with this stupid picture. Of course, now I see the incredible talent he had to draw my likeness and the love that he felt for me in his careful rendering. He could not express love in a normal demonstration that other parents showed their children. But this picture showed his feeling in the best way he knew how to show his love. At that time, I was disappointed at his choice of gifts since I would rather that he would have given me a more age-appropriate gift such as money or toy.

I looked at my father, standing in front of the school’s dining hall, with his drawing of me in my hand. Maybe he was capable of drawing an accurate depiction of my outsides, I thought, but he could never draw a picture of what I felt or of what I was thinking. He had no idea who I was or what I dreamed of becoming.

My Father’s drawing of me. My Bar Mitzva Present

We walked together for a while and I was wondering the whole time why he had not hugged me. All my friends’ parents would hug and kiss them whenever they came to see them on their birthdays. As we wandered through the school yards, passing between buildings along the flower-lined sidewalks, we approached the dining room-kitchen complex. In front of the building were a group of people including the comedian, Danny Kaye. We were always having celebrity visitors at our school because, unknown to the children, was the need to generate money from these wealthy patrons. My father and I were introduced to Mr. Kaye and the others. Suddenly, Mr. Kaye produced a strange looking camera the likes of which we in Israel had never seen. It was a Polaroid and Mr. Kaye immediately took a picture of my father and I. When the picture developed in just a few short minutes, my father was very excited. Both of us were amazed that a camera existed which could almost instantly provide pictures. This Polaroid camera was truly a fantastic mechanical device. In retrospect, I must have inherited my love of gadgets from my father.

When we walked back to the front of the school, Rachel Shapira said to me: “You’re a man today, Gideon. We hope you’ll be a very successful person. Your father is very proud of you.”

“Really?” I asked, looking at him doubtfully. The sparkle I had detected in his eyes earlier was now well gone and I had not intended for the sarcasm to ring through my voice. I hoped that it had not but feared the worse.

“You’d do better if you studied more, instead of playing with those discus and shot puts. Also, you should read more, instead of lifting all those weights,” he blurted out. Well it had, I was sure by the response he gave. I could have studied more, and I could have read more and, not to measure exactly how much more, I was sure that it would still not be enough, and besides the obvious, how did he know how much I studied and read?

“He’ll be fine. Don’t worry,” Rachel reassured my father.

“No! He does not do well at important things.” he said, shaking his head. He was looking at me with his eyes but his mind was looking through me, as if I wasn’t even there.

That was it. That was the moment that changed my life. I loved my father and I knew that he loved me, but there was a great impenetrable black void between us. Neither of us could comprehend the other. At that moment, I felt an enormous bolt as though I had been struck by lightning. I would show my father what I could achieve. I would prove to him that I was good, smart, and I would be the best. One day he would see for himself what a smart, creative person that I actually was.

My father took the picture from me, wrapped it up again with the torn newspaper, and turned to leave. “See you next time, Gideon.” He left me there and had to rush to the road to catch the last bus returning to Tel Aviv, a journey of approximately 30 kilometers.

Rachel held my hand and walked me back to the Kvutza… the house where my room was. I remembered that I had left the tractor running and told her that I needed to see to it. I walked slowly back to the “Pardess”, which means “Orange Grove” in Hebrew, climbed onto my beloved Farmel, and drove it back to the Center. Later, as I walked back to my room, I realized that I did not even have my gift with me. I wondered had he given me a dollar if he would have taken it back. It was at that point that I realized that the portrait of me was not a gift for me at all. Rather, it was for him and he just wanted to show off his work to me. I felt an overwhelming sense of sadness that the day had left in its wake. I would get my gift fifty years later, after my father died.

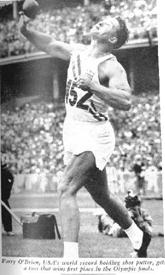

I sat in my room alone with 5 empty beds around me. I wondered what my roommates were doing. They were probably playing with their families or traveling to interesting places. Maybe they were watching soccer games. I looked at the pictures of my heroes on the wall. Rafael Halperin, Mr. Israel in Body Building. Perry O’Brien, the gold medalist of the Helsinki Olympics in the Shot Put. Baruch Habbas, the Israeli shot put champion who broke the Israeli record at 15.07 Meters. What distance had Perry O’Brien thrown, I wondered and picked up the Track Book by Kenneth Doherty. This was an old book, which I had purchased with the little money I earned carrying boxes, and flipped through the pages searching for the record in the Shot Put section.

Rafael Halperin, Mr. Israel. I trained in his Center

Rafael Halperin, Mr. Israel. I trained in his Center

I was amazed to read that Perry O’Brien had thrown the shot put more than 18 Meters which is 64 feet using the English system. What an incredible difference! This was more than 3 Meters (10 feet) farther than Baruch Habbas had thrown. What was he doing to throw so much better then Baruch Habbas? O’Brien was taller but more importantly, he had a different technique. In fact, he began his throw looking backwards. Wow, I thought, what an innovative technique that must be. Why could Habbas not do the same? It must be America. What a dream to be in America.

My Heroes: Perry O’Brien–Shot; and Al Oerter-Discus

I jumped out of my chair to get my world map. It was an old map but who could afford a better one? I looked at America. What a huge country compared to Israel. It must be at least 100 times bigger or even a thousand times bigger, I thought. At the bottom of the map there was a picture of a family driving in a Cadillac car representing America. India had a picture of a cow walking down the street and, for Africa, there was an elephant being ridden by a little child.

My conclusion was that everything and everyone in America was big – at least, bigger than in Israel. They had more land, bigger cars, and even larger people. Perry O’Brien was larger, stronger, and could throw farther than the smaller Israeli athletes.

My thoughts returned to the three meter difference in the shot. I was unable to comprehend this fact. There was such a great discrepancy between the two athletics and their performances. Someone must be able to perform better. Maybe I could? I decided then and there I would represent Israel in the Olympics. Oh, what an amazing dream. I angrily wiped a tear from my eye off the map. I could not afford another map so I had better keep this one clean.

grade. How could I accomplish all that? Could it be possible, I pondered?th I would represent Israel in the Olympics. If I were in America, I was convinced that would be able to throw the shot at least 16 meters. I could see myself driving the Cadillac and what an amazing car it was. I had never seen a Cadillac in Israel. I assumed you had to be a millionaire to be able to afford such a grand car. There was no way I could do this – I had failed 4

For days after that and for the whole Passover vacation, I thought about this dream, this Olympic idea percolating in my mind. Every minute, every hour, all day and night I thought about the possibilities.

Two more weeks went by and at last, the vacation was over. I was so happy to see Hillel, Yakir, Menachem, Eliyaho, and Yosef. They were my best friends. My closest friend, Yakir, unfortunately, was not to live a long life. He was killed, later, flying a mission in the Israeli Air Force.

But that afternoon when all my friends returned to school, they could not stop telling me how great their vacation was at home and all the movies they had seen. I told them how boring it had been here alone each day. Suddenly, Hillel, Yosef, and Yakir noticed the new pictures on the wall.

“What are those above your bed?” asked Yakir.

“Those are my heroes,” I replied.

“What are you going to do with them?” asked Hillel.

“I am going to beat them!” I answered boldly. There was total silence for a moment and then they all burst into hysterical laughter. It was worse than my birthday with my father. I should not have been shocked at their reaction. After all, I knew that I was not a particularly good athlete. In fact, Iris, the beautiful blonde classmate, who I was too shy to tell her of my love, could throw the baseball further than I could. Miriam Sidranski, who was younger and in the class below me, could sprint faster than I could ever dream of. There was no sport in which I excelled and I was unable to defeat anyone, girls or boys, in any sport. So now I had made an announcement like that? Maybe they were right. Well we’ll see, I thought. I can remember how that ridicule fueled the early determination that I would need to accomplish many of my more memorable victories – both in athletics and in business. This early determination would blossom , and to this day continues to blossom, deep within my DNA.

Iris, my early secret love

After they had stopped laughing, I made the following statement:

“My friends, this is what I am going to do:

1. I am going to break the Israeli Records in the Shot-put and Discus.

2. I am going to represent Israel in the Olympics.

3. I am going to study in an American University.

4. I am going to be a Multi-Millionaire.

5. I am going to own a Cadillac.

This was too much for Yakir, Menachem, and Eliyahoo. They left the room to find some other friends to talk about their Passover break. Hillel and Yosef tried desperately to change the subject without making me feel too bad or ridiculous.

I did not tell my friends my last, and most significant, goal. This one was the most important one of all but I did not tell them or anyone else. I am going to prove to my Father just how good I really am!

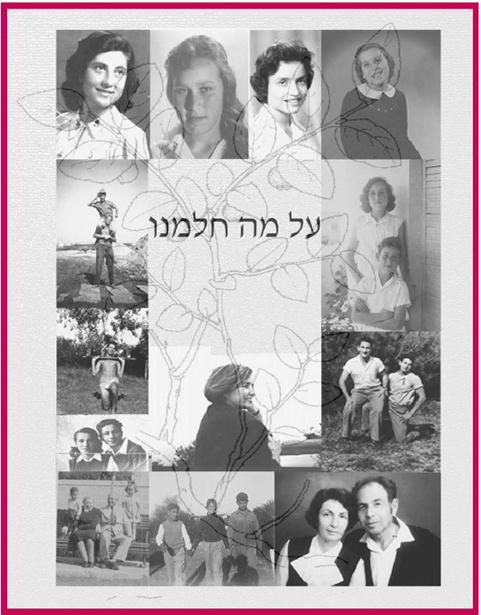

Appendix – 1: Hadassim the Oasis of Dreams

In the middle of the 20th century, during the forties and fifties, the Israeli youth village of Hadassim was the center of an educational miracle the likes of which the world had never seen. Scarred children of the holocaust gathered with scarred children of broken homes to form one community of labor and discourse. Their years together brought them from darkness to light. They not only healed together, but many of them would eventually become leaders and pivotal movers in their diverse realms.

Hadassim’s educational code was: creative dialogue. We, the authors, were fortunate enough to participate in this great educational adventure – one that, in our opinion, has few, if any counterparts in history. The miracle of Hadassim is contained in us, in everything we do. Like the proverbial man of Plato’s Cave, who was able to attend to true reality and thus enlighten his fellows

Hadassim, an enchanted village, a place where dreams were made. This special Youth Village was originally intended as a safe haven for Holocaust orphans and children of broken homes as well as a unique place for learning. As Hadassim children, we lived, studied, and grew to adulthood in a village welding seamlessly its teachers, studies, and culture of labor... Our lives, work and learning were one integral and continuous process. Most of us were children with bright futures but no histories: this disconnect from our past would be countered and healed by a holistic pedagogical method. As graduates of Hadassim, we look back on those precious years with awe and tears as we realize the magic and mysteries that evolved in that special place. Now, fifty-five years later, we’ve decided to write a book about this place, where the broken and lost were bound inextricably with the elite, nurtured together to health, to happiness, and allowed to dream. Its lofty goals and visions enkindled the hearts of mere children, but also represent the birth of a new Nation. We are the first generation of Israel and, as such, we reflect the dreams and aspirations of millions of Jews who came before us.

Our country, Israel, traces its birthplace to the ancient history of the Jewish people, a nation once dispersed throughout the world by overwhelming, conquering empires yet maintaining its traditions for generations. For two thousand years, the Jewish people dreamt of returning to their biblical homeland, the land of Abraham, Although there was always a Jewish presence in the land of Israel, the official rulers were conquering, outside powers -- Persians, Assyrians, Romans, Turks, and British. For thousands of years, the Jewish people were denied first sovereignty then homeland but never lost the dream of Israel, their home.

Most of us were born the year World War II began. Hitler and the Germans had decided on a “final solution” for millions of Jews by slaughtering them by any imaginable -- and the most efficient -- means. History is replete with similar attempts to dissipate or annihilate our people, yet the Jews have survived. Not even the vicious Nazi war machine could prevent those who survived from finding refuge in their ancient homeland of Eretz Israel. Many of these Shoah refugees were bloodied, orphaned from their families, friends, and native countries. In such distressed conditions, they returned to an ancient homeland now occupied by its most recent conquerors.

The United Nation decided that the acceptable solution was to divide a large portion of Palestine so that Arab and Jew would live side by side in what became Jordan and Israel, respectively. Unfortunately, their Arab neighbors felt differently, and chose war rather then Dialogue. The battles continue to this day,

Israel became a Jewish melting pot as Diaspora communities East and West forged a new life from the tattered remains of their oppressed past. This newest United Nations member became an integrated society of Europeans, Americans, South Africans, Australians, all joining with Jews hailing from the Arab World The nation suddenly needed to cope with thousands upon thousands of holocaust survivors -- broken families who had suffered various tragedies, and the “lucky ones” whose loved ones were healthy, and intact. The dream of all Israelis, regardless of age, background, or experience, was a safe haven and home for all, education for their children, and the opportunity for success for all.

Many organizations were struggling at the time for a practical solution for the mass absorption of Diaspora Jews. One organization, WIZO Canada, concentrated on caring for the surviving World War II children. WIZO fundraised to create youth villages for the upbringing and education of holocaust children.

Hadassim was one of those villages. Hundreds of child-survivors were sent there. Dedicated teachers of vast intellectual breadth and various backgrounds also gathered in this wonderful place. Some children, for the first time in their lives, were able to find a safe home. Not only safe, but surrounded by love. In addition to the Shoah survivors came children of broken homes. Lastly, as its reputation for superior education and independence of thought cemented in Israel, the children of many scholars, embassy personnel, and wealthy families were also sent to Hadassim.

Three hundred youths of such varied backgrounds lived and breathed together in a unique society. They studied science, mathematics, literature, and history. They tended to their own lives and wellbeing through agriculture, animal husbandry, cheese making, and other chores of daily life. They pondered questions of philosophy and ran long distance. They wrote poetry and engaged in the visual arts, in music, in dance and theatre. They were pulled in by the vortex of the Dialogic idea, the spirit that governed the most enlightened educational philosophy of the time, deeply ingrained in their teachers --an idea that enabled the integration of life and knowledge, of the mind, senses and feelings, of teacher and student. A free, intimate and creative dialogue reigned between every individual, according to the network principle -- the very principle underlying the communicative function of the brain, allowing for infinite creative development. They made their own “government”, and learned how to direct themselves ethically to achieve cooperation and practical solutions for all. Grown into adulthood, these children came to epitomize the first generation of the State of Israel. As the first children’s group of the newly established state of Israel, they represent a unique integration of constituents which had never existed before and never has since.

Our story is the story of the Generation of the State, the generation forged during the founding of the State of Israel. Two generations of Zionist life in the land of Palestine had preceded ours: the Founding Generation, led by Ben-Gurion, and the Palmach Generation, led by Moshe Dayan and Yigal Allon. The iconic generals Yitzhak Rabin and Ariel Sharon were also groomed in the Palmach days.

We are the Third Generation, born in the thirties and forties. One after another, the pieces of our adolescent landscape unfolded with WWII and the Holocaust, the influx of illegal refugees from occupied Europe, the struggle against the British, the War of Independence, a still more earth-shaking wave of Mizrachi and Ashkenzi immigrants and still further Arab attacks on the newborn state. After the Suez War, in the fifties, our leaders claimed that the era of war had given way to the era of peace. We, of course, took these claims seriously, though they had no basis in reality, so we never considered the army our highest calling – as the Palmach generation had. We pursued other interests, namely: science, business, sports and art. Beyond the communal life of the nation, each of us delved into our own personal experience, and these individual narratives will be presented in full, unvarnished and whole, as without them none of us can truly be known. While the Hadassim tale deals in a miracle, the tales of its students are sometimes quite difficult to bear. Some of our parents were murdered in the Holocaust, while still others fell in the War of Independence. The remainder survived to build the state, handing their flag down to us at the twilight of their days.

In order to create the conditions for true dialogue among Hadassim students, in order to stir in them a life of creativity, Jeremiah and Rachel Shapirah determined that students would be selected in equal numbers from three groups: Holocaust survivors, children of broken or troubled homes, and lastly those children of a comparatively privileged status – heirs of comfortable hearths and homes whose parents were simply too busy to tend to them, for a variety of reasons. The three groups integrated well: the rich kids grappled with new realities; the troubled kids were introduced to better realities, and learned in their guts that they could succeed if they would only make the effort; and the holocaust survivors encountered the new, versatile world of a versatile Israeli identity. In the end, these children of the Holocaust became Israelis, while the troubled kids ascended to the elite and the elite learned to live uncorrupted by their privileges.

Many of the kids in Hadassim who’d lived through the Holocaust were, in fact, the moral and intellectual elite of our generation. Not only had they been better cultivated in the European Diaspora, but their hard-won battles for survival had endowed them with moral and psychological virtues of far greater reach. In order to harness their latent strength, however, they first needed a warm and understanding home; they needed friends who would keep close to them rather than labeling them “soaps” -- a cruel jibe at their near-immolation at the concentration camps – as was so much the custom in the cities and Kibbutzim. They needed teachers who would also be friends.

The children of the Holocaust were given all of these things in Hadassim.

Hadassim’s miracle of miracles is the story of Gideon Ariel, the co-author of this book. Miracles happened to all of us, to Shevach Weiss, Micha Spira and me, but Gideon comes in first by everyone’s assessment. As we near the end of our story, when the reader is already acquainted with our journeys and dreams, we now offer him the opportunity of a Buberian dialogue with the singular phenomenon of Gideon. Should Hadassim one day be regarded as a model, everyone will have the chance to reach where Gideon has reached.

At the beginning lay the genes, excellent in quality, without which none of the rest would follow. But they were consigned to a hostile environment, reminiscent of the story of baby Oedipus, whose father (the king) commanded that he be drowned in the river. In this case, the king had him tortured day and night, and the baby wailed and cried.

But then the most astounding thing happened: having pierced through thick walls, outside the screaming had transformed into music of ineffable beauty. A herd of men assembled and cried: “Let him suffer! The music is joy to our ears!”

This is Gideon’s special music.

We are talking here about a man whose father beat him body and soul, from the moment his son was born to his last days on earth; a boy who observed in horror-laced curiosity as his mother made extramarital love to the mayor of Tel Aviv and the city’s chief engineer; a boy who looked on as psychiatrists dragged his healthy mother from her home and into a mental ward; a boy who repeated the fourth grade, who was rejected from the Technion, who was barely accepted at the seminar for physical education teachers at the Wingate Institute.

No one in Hadassim, not even his close friend Chilli, had known the details behind some of Gideon’s grueling history. Gideon himself remained ignorant of some of the facts uncovered in this book. There may even be something left to discover in all of it, but as our sages of old have said: it’s not for us to lay bare every secret.

Given such a ghastly early childhood, what kind of future did he have waiting for him? Whoever had known him during that period could only have hoped that he wouldn’t fall apart completely. That was precisely his father’s attitude – Moshe, the only man in the world who had access to all the information, but who couldn’t properly grasp any of it. Moshe Ariel made an effort to admonish his son at every turn, “You’ll never amount to anything!” evidently intent on spurring him to learn a profession and avoid the double penalties of poverty and violence. His father didn’t know then that Gideon – like the Hadassim phoenix and Hugo’s L’homme Qui Rit – is his own miracle, the miracle of a freedom that transcends every barrier, the miracle of intellectual sovereignty. The latter characterization should go well to dissuade the reader from any simplistic misreading of our main thesis.

Because of the values he absorbed in Hadassim -- principally the value of self-examining dialogue (“Know Thyself”[1]) -- and given tremendous willpower and perseverance only few can possess, Gideon turned himself into a champion athlete, representing Israel in two Olympic Games, and pursued a doctorate in the U.S. before developing a new applied scientific field: computerized sports bio-mechanics.

It has been left to the noblest among us, singular in history, to open up new scientific vistas. Gideon was one of them. An achievement of that sort requires shifting the given paradigm, a venture reserved for men of exceptional caliber. Gideon may not be Einstein -- but Einstein wasn’t Newton, either.

Gideon went on to help the USA through two Olympic Games, and he is personally credited for paving the way for several American athletes who went on to break sixteen world records. Today he serves as the biomechanics consultant for the Chinese 2008 team, though he helps train the Israeli team as well.

Without Gideon Ariel’s story, the story of the Hadassim Miracle would be incomplete. But his story is enough proof for anyone that the Hadassim model would serve brilliantly as the cornerstone of a new educational paradigm.

When Gideon was 17 years old, the village of Hadassim hosted an event -- the Hadassiada – wherein athletes from WIZO institutions all across the country competed in a myriad of sports. Gideon dominated the shot-put event (16.55 meters). It was clear that Hadassim had a star in its midst. Hours later, Gideon and Iris were watching as Uri Glin, a relative of Iris’, broke the Israeli discus record. Gideon boasted that he would overtake that record soon enough, and those around him forgave him for harboring what they thought were delusions of grandeur. Gideon has always been shy by temperament, but when he dialogues with his own dreams his chutzpa knows no boundaries. It suffices to say, that brand of chutzpa has always led humanity forward (and driven the establishment gatekeepers crazy).

“I’ve achieved everything I set out for my life,” Gideon says. “If I believe in something, I go all the way. I have a reservoir backup for everything I do – a driving will.”

Gideon was serious about breaking Glin’s record, and he needed to dialogue with his discus in order to succeed. “I slept with my discus tied to my hands for years. Whenever I trained, I always asked it, ‘Fly a little farther, just a little farther…’ One time Gilead Weingarten[2] came by the field and heard me talking to the discus. He thought I’d completely lost it. I pretended it was all a joke, of course; but in truth I was completely serious about it – I could hear the damn thing talking back. I knew it was abnormal, but that didn’t matter much to me. I kept visualizing myself standing on the winner’s platform and holding the discus. I did the same thing with the shot-put. I wasn’t familiar with the concept ‘dialogue’ yet. Now I understand that’s what I was doing.”

By the 12th grade, there was no doubt that Gideon was the leading athlete at the discus and shot put in the country. Uri Glin had begun to reflect about Gideon’s ‘joke’ – that it was no joke at all.

Despite his immense intellectual potential, his childhood traumas had blocked his synthetic-analogical programming. He ended up failing the bible and Hebrew literature state exams. I feel partly responsible for those failures, as I’d already left Hadassim by that time (during 10th grade); our dialogue, which began early on in my grandfather’s apartment on Lilienbloom St., was only reignited after a period of fifty years, when we decided to co-write this book. As for the rest of his academic performance, he managed to receive high marks in physics, biology and math; his digital-analytical side was strong enough to break through his psychic barriers. He was especially skilled at Biology. These accomplishments brought home to him the following insight, perhaps the most important one: “If I can’t excel at anything, then I might be dumb. But if I can excel in at least one field, it just means I have some issues...’ Studying biology with Micha Spira and Chemistry with Gideon Lavi made this point ever clearer.

Still, having failed two of his exams meant he couldn’t study at the Technion. But even that was for the better. He wasn’t ready for that kind of experience yet. In those days, in the sixties, he was better off somewhere else – in the U.S., where the software and computer industries were about to go through their nascent stages. The opportunity wasn’t quite there for him yet in 1958, anyway. On the advice of his trainer, Yariv Oren, he turned to study at the Wingate Institute (at the seminar for physical educators), where he prepared for the Rome Olympic Games. He initially failed the entrance exam for the school, but Yariv pulled some strings and managed to get him in.

Gideon trained vigorously for two years. The qualifying matches were held in 1960. The current shot-put champion, Uri Zohar, was there, and Gideon let it be known to all the

journalists that he intended to break the Israeli record. And he did just that, at the very first trial, breaking Uri Zohar’s spirits in the process: the old champion ran to the bathrooms and cried. Then, the next day Gideon broke Glin’s discus record – by three meters (!). Needless to say, Gideon qualified for the national team – a dream which only recently had seemed impossible. Unfortunately, his performance in Rome was lackluster, far below his standards.

“Failing at that point, just when I’d reached the world stage, was a residue of my father’s sabotage. I became paralyzed: my hand just wouldn’t move right. I was much better when I was training.”

John Walker, the American trainer, offered him scholarship at the University of Wyoming, but Gideon declined: he was looking forward to his military service. He would continue to train in the army, and he even gave some lessons to some of the most senior IDF commanders -- including (then) Major General Yitzhak Rabin, Major General Ezer Weitzman and Colonel Arik Sharon. He left the IDF after two and half years, writing to Walker about the scholarship he’d offered him. The American trainer sent him a one way ticket.

“I decided to leave the country, along with all my private issues there. My friends tried to warn me about the scourge of emigration. But my desire to escape from my past was stronger than any fear of being accused of abandoning the country. My mother was still alive then, still in a psychiatric ward. If anything, I felt guilty for abandoning her. Nobody came to see her, as she couldn’t recognize anyone.

“I arrived in New York, where I got on a four hour flight to Wyoming. I had five dollars in my pocket. Walker had arranged to have a bus pick me up and take me to the university – where it was incredibly cold. I didn’t have any of the right winter gear, so I was absolutely freezing.

“I barely knew any English at the time, so I took sewing, drawing, physiology, physics – velocities and accelerations – the Mickey Mouse courses, basically. College athletes don’t really need to study much in America. I still took the classes seriously, so I was able to make great advances, and not only in sports.

“I was rather lonely and miserable for a while; I even told Walker I wanted to go back home. I had a girlfriend in Israel, Yael Tzabar, a member of the Inbal dance troupe. She was very beautiful, and I was crazy about her. We didn’t quite fit as a couple, but it was important to me to be seen with a beautiful woman. Walker suggested that I help arrange a scholarship for one of my Israeli friends, so that way I’d have someone with me in Wyoming. I invited Gilead Weingarten, the long jump athlete, and we ended up sharing a room together in the athletes’ wing. The temperature in February 1961 was ridiculous: 50 below zero! On the other hand, we were getting everything for free, so…

“I spent most of my time throwing the discus and shot put around. My discus record had been 55 meters, but I managed to reach 58 meters at the time. Sadly, that record wasn’t validated in Israel.

“Yael finally joined me, and soon we were married and had a daughter. I was very much in love. Yael shared my father’s dominant qualities. She eventually divorced me, after she’d had enough of my addictions – for study, for my training, and for working on my inventions.

“When it came time for the next Olympic qualification rounds in Israel (for the Tokyo games), no one stood a chance against me. My throws never fell below 53 meters, and no one else could climb above 47. In Tokyo, however, I let my nerves get the better of me again. My performance was pitiful. Athletes are supposed to prepare like professionals, adjusting their nutritional intake when necessary, but I let myself binge on deserts and I gained weight. You just can’t compete on the world stage without professional coaching. I trembled with fear when it came time to face the world champions. They were all two meters tall (6’5”) and looked like they weighed 100 kgs. Their throws were better than mine – 20 meters – setting new records.

“I just wasn’t ready for what I encountered in Tokyo.”

“I was a good student at Wyoming. I finished my bachelors in 1966. Both Gilead and I did very well academically. I remember him asking me about getting gowns for the graduation ceremony.”

‘What do we wear underneath?’ I asked.

‘Underwear, I suppose,’ he replied, grinning.

“So we only wore underwear underneath our gowns, giving everyone a perfect view of our hairy legs. We were the joke of the graduation party. Anyway, we’d both done well enough to get scholarships for graduate school. I went to Mass for my doctorate, and Gilead went left for Minessota.”

Gideon was ready for an academic challenge. The genetic power stifled by his father in early childhood now broke loose, like a volcano: Gideon decided on a joint doctoral program, in biomechanics and computer science. His was the virtue of the anti-Scholasticism Renaissance man who breaks through the culture’s mind-body dichotomy, and he displayed that in full via simultaneous engagement in research, intellectual development, creation and business -- all the while continuing to train for athletic competition.

Given the invincible narrow-mindedness that prevails in academia, Gideon will no doubt be met with envy for his Promethean abilities and success, for using his skills to make money. At Boston, he specialized in Cybernetics[3] and software development – he was among the outstanding specialists in that field for a good period – developing software for monitoring the nervous system.

“I finished my PhD in biomechanics at the age of thirty. I was concurrently enrolled in a physiology program at the Bloomington medical school in Indiana, and when I finished with that I began an engineering program – starting as a freshman. I didn’t let my lecturer in on the fact that I had a PhD, along with a university job of my own. One day, I had to leave in the middle of class in order to teach a seminar on the other side of campus, so I let my professor know about it. ‘You’re a lecturer?’ he asked, looking slightly puzzled. That weekend I sent him ten of my publications, so when I came back to class on Monday he made it a point to say, in front of everyone: ‘Dr. Ariel, you don’t have to take anymore tests.’ He was angry at me for not telling him about my record. I’d already studied dynamics, statistics, statics and liquids…”

As a first-handed man, Gideon has been motivated by his spiritual creativity, the ultimate source of his business success.

“Money wasn’t my motivation. If it were, I wouldn’t have amounted to much. I hate running after money – it’s the death of creativity. There was always the need for it, of course, but I didn’t just sit there and think in terms of ‘how to make money’. I got patents for my inventions, some of them very lucrative, but I never bargained. At the time I could probably have doubled my capital, if I really wanted to.

“My financial situation was pretty bad when I finished my doctorate. My tuition was free, but I was getting a very low stipend as an athletics trainer, and I had a family to think of – my wife and my daughter, Geffen. Geffen would later die of leukemia.

“Sometime in 1969 I ran into Harold Zinkin, ‘Mr. California,’ who had made tons of money running his own gyms. I gave him advice about developing a machine that could substitute for weights, eliminating much of the accident risk. He was very enthusiastic about my idea, so together we built the first ‘Gladiator’ model. We sold fifteen machines in the first year, and by 1971 the number climbed up to a thousand. At that point I built an improved model, the “Centurion,” and received a royalty check for a hundred-thousand dollars from Zinkin. When I showed the check to all my teachers and colleagues, naively hoping to spread my happiness around, I got a lot of dirty looks. Right there I learned a harsh lesson: never talk about money with anyone. Rather, if you tell people that you’re losing money, everyone will be your friend.

In 1972 Gideon received his PhD in Biomechanics -- the same year he invented air-soles for running shoes -- the same air-soles that have paid him fifty million dollars in royalties over the years. He invested most of his early money in a biomechanics lab, the most sophisticated of its kind in the seventies. From all over the world, States, corporations and sports institutions have looked to Ariel’s laboratory for their projects. He got his PhD in computer science in 1975, and became a college professor.

As Gideon ran around campus with million dollar checks in his pockets (he didn’t have time to visit a bank), what was first only envy of him turned into searing hatred. Two professors sued him in the early 80’s for exploiting his academic position for profit; they demanded that he contribute half his business earnings back into the university. By the end of the ensuing trial, the district court judge said that “if Mr. Ariel was obligated to compensate the university, the university must, in turn, compensate Isaac Newton.” Gideon resigned from his teaching position a short time later, dedicating his full efforts to his inventions.

Sometime at the start of 1968, Gideon made an appointment with Walter Carol, a physiology professor. The blond girl who let him into the office was a striking beauty. Gideon asked if he could speak with the professor, but the girl informed him the he was in the wrong office and abruptly closed the door in his face. “What a bitch!” Gideon thought to himself. That would prove to be only his first encounter with Ann Penny -- his future wife. Soon enough, Gideon enrolled in an advanced statistics course, and one day the lecturer asked a question that no one seemed willing to answer. Suddenly a hand went up, and there she was – the same beautiful girl from the “wrong office”. Gideon knew he had to have her, and he courted her with unassailable confidence until she finally fell for him. They’ve been inseparable ever since. In Ann, Gideon had found the mother he never had, and more. She’s his partner in everything: in the development of his ideas, his dreams, his business – even in this book. They finally married each other after thirty-five years of close, creative dialogue.

When Gideon felt secure enough in his abilities, he began working on his dream project. For a long time, Gideon had been developing the notion of “dynamic shifting force,” an idea that prodded him from the moment he started tying chains and food cans to his weights. By the time he’d carved a life for himself in America, he was already thinking in more advanced terms: “dynamic variable resistance”.

Stephen Plaginof, his Biomechanics professor, had shown him how to measure resistance on every joint in the body. Such techniques had evidently already been developed in Germany during the 19th century, and used by gymnastics trainers ever since. Gideon wanted to go a step further and computerize the measurement process. Personal computers weren’t around yet, just the mammoth-sized ones, and these were rather expensive – $10,000,000 each. So Gideon built a small personal computer, perhaps the first in the world. In 1974 he showed it to Professor Ervine Dardick, a famous vein surgeon and inventor of a tube used for heart bypass surgery -- a surgery only he could perform at the time. He was also in charge of sports medicine for the Olympic Committee, and he was very excited by the PC. He, in turn, showed it to William Simon, treasury secretary (and head of the Olympic Committee), who showed it to William Kasey – the CIA director. In the end, Kasey and Simon teamed up to form a new company, Life Systems. They felt they could make millions with the computer, but they decided to pay for a ten-thousand dollar marketing survey, just to test the ground (and avoid an unnecessary loss). They dropped the project when the survey came back negative, and left the computer with Gideon.

In 1975, with that same computer, Gideon built a fully computerized system in line with what he had originally conceived in Hadassim and envisioned in the U.S. (Among other things, he applied a cinematic slow-motion graphics technique.) Gideon’s system identifies and analyzes an individual’s physical skills, then trains the athlete by tapping into his nervous system and shifting resistance levels according to changes in muscular force within a range of motion. Rather than having a trainer in a gym select the weight at each turn, Gideon’s patent allows a machine to determine the proper weight changes.

Gideon started by taking his invention to scientific conferences and talking to sports journalists. Those were the days when Biomechanics specialists treated him with the utmost contempt, branding him a crook. He was even sued at the time, but he won the case.

In 1976, Gideon was appointed scientific head of the American Olympic Committee. The volleyball team, trained by an Israeli named Arie Zelinger, was ranked 50th in the world at the time. After they started using Gideon’s technology, however, Zelinger’s team managed to make its way to the top, winning the silver medal. (The Chinese won the gold.) Later, in 1984, Gideon traveled to China. He met with Professor Chang Yu, and together they outlined a collaborative research project – one which ended up lending a great deal of credibility to his invention. He was also invited to present his technology in East Germany.

Today, Gideon’s system is used the world over, for athletic diagnostics and training as well as other biomechanical applications. Governments use it to train their fighter pilots; NASA uses it to train their astronauts; President Reagan used it to improve his health while in office.

In April 2006, the University of Massachusetts presented Gideon with the graduate’s medal for special contribution to science, an honor bestowed every five years to its prominent scientific alumni. The university which had once sued him, which had once sought to tear him down socially and financially, was now commending him in the most extravagant way. Gideon has made it big in the world, and there’s still more to look forward to.

Gideon rose from the abyss up to the highest summit. Scars remain, of course, as with anyone who ever accumulates them. But the reason Gideon overcame those early traumas, in the first place, brings us back to Hadassim. His years in the village unleashed his colossal reserves of will and brainpower from the prison of his parent’s home in Tel Aviv.

We believe that everyone has potential, each in his own realm. Often it remains hidden, oppressed in infancy, dulled by a childhood mired in pain, drowned in hostile environments. Hadassim applied the optimal model for liberating such hidden potentials. We can only hope for that model to be further studied and used for the betterment of mankind.