Journal of Medical Systems, Vol. 20, No. 6, 1996

of Kinematic Recording InstrumentsA

Comparison

Richard H. Eckhouse,',* M. Ann

Penny,2 and Ruth A. Maulucci3[Back to Home Page]

Kinematics, the study of motion, is employed in numerous

biomechanics and human performance investigations. The types of instrumentation used in

these studies vary at fundamental technical levels, making it difficult to relate results

from studies carried out at different laboratories using different instrumentation. A

project was designed to compare two commonly used types of kinematic recording techniques,

i.e., the 6 df electromagnetic tracker system and the video motion analysis system. A

four-level testing and comparison method was conducted involving static and dynamic

inanimate objects, as well as human subjects under static and dynamic conditions. It was

demonstrated that for rigid body inanimate objects the two systems produce nearly

identical values under stationary conditions and are comparable under moving conditions.

The systems show only trivial discrepancies in static human body measurements, and perform

in qualitatively similar ways on human motion.

KEY WORDS:

Kinematics; electromagnetic tracker; video motion analyzer; reaching.

Kinematics, the study of motion, is employed in numerous

biomechanics and human performance investigations. The types of instrumentation used in

these studies abound, and vary considerably at fundamental technical levels. An early

review of recording systems for biomechanical analysis is found in Ayoub.0) A later

comparative analysis of kinematic measurement systems given in Tyson and Das.(2) Such a

variety of devices makes comparisons among studies conducted at different laboratories

with different instrumentation difficult, and limits the usefulness of the results.

INTRODUCTION

An important and much

explored area of biomechanics is guided limb motion or reaching for a target in the

workspace of the arm. A brief survey of the literature revealed that there are two

categories of instrumentation that are very common choices for reaching studies, these

being electromagnetic tracking and video motion

To whom correspondence should be addressed.

2Computerized Biomechanical Analysis, Trabuco Canyon, California. 3MOCO, Inc., Scituate,

Massachusetts.

'Mathematics

and Computer Science Department, University of Massachusetts-Boston, 100 Morrissey

Boulevard, Boston, Massachusetts 02125-3393.

]Go to Top of Document[

440

Eckhouse,

Penny, and Maulucci

analysis.

The question arises as to whether the results of studies employing these different types

of devices are compatible. Thus, a comparison of the performance of the two types of

systems should prove to be of general value.

The first category of systems consists of electromagnetic

trackers.(3-7) These provide the 6 df of a moving sensor relative to a fixed source,

employing technology that uses low frequency magnetic fields to make these measurements.

These systems record angular information directly, with sensors that are attached to the

skin surface. There can be slippage of the sensors, particularly in the twist motions,

problems can arise due to interference from metal in the environment, and there can be

delays due to filtering.

The second category, video motion analyzers, is made up of two- and

threedimensional human performance systems.(8,9) Body segment points are located with

retroreflective spherical markers attached by double-sided tape, and the systems

automatically track these markers through successive frames, assuming adequate background

contrast. Each camera sees a marker in two dimensions; a marker must be in the field of

view of at least two cameras simultaneously in order for its threedimensional location to

be calculated. In some systems, if a marker becomes occluded, the system automatically

supplies the missing point by interpolation. Typically, system resolution and accuracy are

high. Software for data capture, threedimensional calibration, computation of the

three-dimensional coordinates of the target markers, interactive graphics for plots and

stick figures, statistical routines, and signal processing is often available, and data

reduction is rapid. Some of these systems demand a controlled environment, since the

system requires multiple electrical outlets, a room with a matte finish, heavily draped

windows, and fluorescent light. An optional feature in some of the systems is that it is

possible to record without markers and then manually digitize each frame; the trade-off,

however, is that the operator must locate joint centers. As a compromise, some systems

allow points of interest on the subject to be tracked semi-automatically without markers,

requiring that the operator initially identify the desired points; the system then

predicts the location of these points in subsequent frames.

There are many examples of reaching studies that used electromagnetic

or video systems. The use of electromagnetic monitoring to quantify eye-head-hand

coordination during reaching tasks has been reported.(10) Free(11) and constrained(12) arm

and leg reaching movements were examined using a four-receiver electromagnetic device. A

computerized system centered around a 6 df electromagnetic device was build by Eckhouse et

al.(13) to facilitate reaching in preschool children with cerebral palsy by modifying the

trajectory of the arm. A magnetic kinesiograph was used to compare slow arm movement

trajectories in patients with Parkinson's disease to those of normal subjects.(14) An

electromagnetic transmitter was used to examine whether the straight line paths of

two-joint planar reaching movements reflect constraints associated with perception or

movement production.(15) High-speed film was digitized to discuss the effects of load and

variation on the autoregressive integrated moving average model for muscle signals.(16)

Three high-speed cameras were used to identify the curvature-speed relationship in the

reaching movements of infants.(17)

]Go to Top of Document[

441

Instrument Comparison A project was

designed to compare these two commonly used types of kinematic recording techniques, i.e.,

the 6 df electromagnetic device and the video motion analysis device, in guided limb

motion tasks. The specific member of the former group that was selected was the Ascension

Flock of Birds (FOB), and the Ariel Performance Analysis System (APAS) was chosen from the

latter group. The goal was to determine how close these two very different types of

devices operate, and whether the results obtained from one system could be compared with

the results from the other. There are several possible sources of measurement errors or

differences for the two systems, particularly in applications involving human subjects.

They could be caused by system setup, sampling rate, resolution, accuracy, receiver and

marker attachment to the body, and receivers and markers moving with the skin surface.

Digitizing errors and magnetic field corruption contribute additional complicating

factors. To isolate the possible different causes, a four-level testing and comparison

method was conducted involving static and dynamic inanimate objects, as well as human

subjects under static and dynamic conditions.

this discussion, trajectory refers to a time

series of points that define the position of a translational coordinate or angle

throughout its interval of motion. A functional reach is a task oriented limb movement,

such as reaching for a target. With regard to human subjects, x is the medial/lateral, y

is the anterior/posterior, and z is the superior/inferior direction.

Throughout

is a real-time, electromagnetic mechanism that

provides the location (x, y, z) and orientation (a-azimuth, e-elevation, r-roll), i.e., 6

df, of moving receivers relative to a fixed transmitter. Output is in the form of time

series signals that uniquely determine the location and orientation of the receivers

relative to the transmitter. The receiver is a small cube of about 2.5 cm that weighs less

than 0.03 kg. The transmitter assembly is a larger cube about 9.5 cm weighing about 1.8

kg. The system provides hemispherical measurement within a 1 m radius. System resolution

is 0.1 deg rotational and 0.08 cm translational; accuracy is approximately 0.5 deg for

rotations and 0.25 cm for translations. Sampling rate is 100 Hz per receiver. The output

is connected via a high speed asynchronous serial RS-485 communications adapter to a

microcomputer for immediate processing. Up to four FOB receivers were used simultaneously

in this project, each receiver attached to an individual object or body segment, allowing

the recording of the three translational and the three rotational coordinates of that

object or segment. Thus, the exact location and orientation of the object or segment was

specified throughout the interval of motion. FOB The

The APAS is a three-dimensional video motion analysis system. One or

multiple cameras can be used, markers are optional, and automatic or manual digitizing is

supported. The image sequences are stored, in picture form, on a computer for

]Go

to Top of Document[

442

Eckhouse,

Penny, and Maulucci

subsequent

processing. The system permits frame grabbing, frame retrieval, data compression,

smoothing and filtering options, and zooming. Viewing and graphing modules for the

digitized activity, measured or computed, are available. Two variable shutter cameras were

used in this project, each operating at 60 frames per sec. Several types of reflective

markers were used to assist in identifying the points of interest: a finger cot with

reflective tape, large and small reflective balls, and a splint with a small reflective

ball attached to each end. Selected points were digitized in each frame, producing the Y, y, and z translation trajectories, i.e., the location of each coordinate

over time, of the points.

could be

synchronized and used concurrently. Each trial proceeded as follows. A large light

emitting diode (LED) display was placed in the viewing field of the two APAS cameras. The

two cameras were started. The trial number was presented to the cameras manually by

placing a clipboard containing the written number in front of the cameras for a few

seconds. By means of a keystroke, three events occurred simultaneously, namely, a tone was

emitted, the LED display changed, and FOB data collection was initiated. The data were

collected for 6 sec. At that instance, the LED display changed again and the FOB stopped

automatically. The cameras were turned off manually. Thus, the two APAS frames in which

the LED changed corresponded to the initial and final data points of the FOB. This allowed

the signal points of one system to be matched in time with the signal points of the other

system, and in addition synchronized the two APAS cameras.

FOB and APAS A method was devised so that the

A formal protocol was developed to permit comparison of the two

systems. System performance was examined at four levels, each increasing the difficulty of

obtaining system compatibility. The first level, termed static inanimate, was to determine

the x, y, and z translational distances between two fixed points, the fixed flexion angle

formed by a goniometer, and the fixed twist angle displacement made by a goniometer. In

the second level, dynamic inanimate, trajectories were obtained for the three translation

signals of a randomly moving point, the randomly changing flexion angle formed by two

rods, and the randomly changing twist angle produced by a rod. For the third level, static

animate, a human subject held his or her arm in various fixed positions intermediate to a

functional reach; the three translational distances between selected body landmarks, joint

flexion angles, and angles formed by body segments and the coordinate axes were obtained.

At the fourth level, dynamic animate, the human subject made simple functional reaches;

the x, y, and z translation trajectories of selected body landmarks, joint flexion and

twist angle trajectories, and trajectories of angles formed by body segments and the

coordinate axes were acquired.

443

Instrument Comparison Levels III and IV were conducted with human subjects. No attempt was

made to control for age, gender, handedness, stature, or weight, since the objective was

simply to compare data simultaneously acquired by the FOB and the APAS. Informed consent

was obtained from each subject prior to the start of any testing.

II. Dynamic Inanimate

Level IA

Level I.A was to use the FOB and the

APAS to calculate the Y, y, and z translational distances between two

fixed points. An APAS large reflective ban was attached to the top of each of two FOB

receivers, and the two marker/receiver combinations were set at oblique x, y, and z

distances. The x, y, and z distances were measured three times in short succession with a

steel measuring tape, calculated for each sample acquired by the FOB during the 6-sec data

collection interval, and calculated for each frame acquired by the APAS during the

six-second data collection interval. Three trials were made, with the marker/receiver

combinations placed in different locations each time.

Level LB

Level I.B was to calculate the fixed

flexion angle formed by a plastic full-circle universal goniometer. An APAS large

reflective ball was attached to the top of each of two FOB receivers. One of these was

placed at each arm end of a goniometer, and one APAS large reflective ball was placed at

the vertex of the goniometer. The goniometer was set to an arbitrary angle. The goniometer

angle was read three times, and was calculated for each FOB sample and each APAS frame

during the 6-sec collection interval. Fourteen trials were made, with the goniometer at

different angles and in different states of rotation and tilt relative to the APAS

cameras.

Level I.C

splint that had a small reflective ball attached to

each end, with the receiver wire perpendicular to the splint. The edge side of the splint

was placed along one arm of a goniometer, with the center of the edge at the vertex of the

goniometer. Note that in this configuration, if the splint combination were attached to a

segrnent perpendicular to the goniometer at its vertex, the flexion angle of the

goniometer arm would be equivalent to the twist motion of the segment. During the 6-sec

data collection interval, the goniometer was set in succession to two different

arbitrarily APAS Level I.C was to calculate the fixed

twist angle displacement made by a goniometer. An FOB receiver was attached to the center

of the flat side of an

]Go

to Top of Document[

444

Eckhouse,

Penny, and Maulucci

frame in which they occurred, i.e., for approximately 3 sec each. The means of the two

angle values were used to calculate the mean twist angle displacement. Eight trials were

made, with the goniometer skewed differently with respect to the APAS cameras. APAS

selected

angles. The two angles were read three times each, and calculated for each FOB sample and

Level IIA was to obtain the trajectories for the x, y, and z

translation signals of a randomly moving point. An APAS large reflective ball was attached

to the top of an FOB receiver, and the marker/receiver combination attached to the end of

a long rod. The rod was manually translated randomly in three dimensions during the data

collection interval. The x, y, and z trajectories of the marker/receiver object were

calculated from the FOB and APAS data, and then graphed. Four trials were made, with

different random motions and speeds of the rod. Level II.A

Level II.B was to obtain the trajectory of a randomly changing

flexion angle formed by two rods. An APAS large reflective marker was attached to the top

of each of two FOB receivers. One marker/receiver combination was put at each end of two

joined rods, and an APAS large reflective marker was put at the vertex of the joined rods.

During the data collection interval, the flexion angle of the rods was changed while the

rods were translated, all with continuous random motion made manually. The flexion angle

trajectory of the rods was calculated from the FOB and APAS data, and graphed. Three

trials were made, with different translating and angle motions of the rods. Level II.B

data, and graphed. Three trials were made,

with different translation and angular motions of the rod. APAS Level II.C was to obtain the trajectory of a randomly changing

twist angle of a rod. An FOB receiver was attached to the center of an APAS splint with a

small reflective ball at each end. The splint was put on the rod as a crosspiece. During

the data collection interval, the twist angle of the rod was changed while the rod was

translated, all manually with continuous random motion. The twist angle trajectory of the

rod was calculated from the FOB and Level II.C

Level III consisted of a human subject holding his or her arm at

the initial, intermediate, and final positions of a simple three-dimensional functional

reach. Targets of various shapes and in various locations within the workspace of the arm Level III

]Go to Top of Document[

445

Instrument Comparison from a seated

position were used. All reaches were made at natural speeds, as established by the

subject.

The basic reach consisted of a decision to access a target in the

workspace, followed by visually locating the target, and then using visually guided motion

to bring the arm naturally to a successful access of the target. During the reach, the

torso remained stationary and against the chair. The proximal end of the clavicle was

fixed, meaning that it did not translate. Clavicle, shoulder, elbow, and wrist motion was

allowed. Accuracy was important, reaction time was not, and movement time was whatever was

natural for the individual. The initial position was with the upper arm perpendicular to

the ground, the elbow at 90 degrees, and the forearm midway between pronation and

supination. The final position was with the pad of the middle finger on the target and the

palm facing away from or toward the subject. An intermediate position was any position

between the initial and final positions that occurred naturally during the reach. The

forward distance of all targets from the shoulder was the same and was determined as

follows. It was the distance at which the shoulder had to be placed from a point that was

16 cm above and laterally aligned with the shoulder to induce full arm extension to touch

the point.

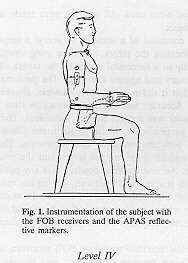

angles. Figure 1

illustrates the subject instrumentation, complete with receivers and markers. Six subjects

were used. Three targets in different locations and requiring different final positions

were used. For each target, the subject assumed the three positions for six seconds each. dial/lateral rotation twist The subject was instrumented with four FOB receivers, one on each

segment of the arm, i.e., the hand, forearm, upper arm, and clavicle. The receivers were

numbered distally to proximally 1, 2, 3, and 4. It was found that the best results were

obtained by first mounting the receiver on a tongue depressor, then securing it to the

body segment with medical tape, and then placing a light net stretch-and hold first-aid

sleeve over it. The subject was simultaneously instrumented with several APAS reflective

markers, i.e., a finger cot, forearm splint, large elbow ball, upper arm splint, large

shoulder ball, and large clavicle ball. The large elbow, shoulder, and clavicle balls were

not placed on the joints, but rather served as a cue for locating the joint centers during

later digitizing. The forearm and upper arm FOB receivers and the corresponding forearm

and upper arm APAS splints were placed at the same point longitudinally on the limb

segment so as to minimize actual differences along the segment of the forearm

pronation/supination and shoulder me

The following calculations were made from both the FOB and APAS data,

using all samples or all frames of the 6-sec data collection interval. The x, y, and z

translational distances between each adjacent pair of FOB receivers was calculated. Wrist

flexion/extension, wrist radial/ulnar deviation, and elbow flexion/extension angles were

also calculated. Finally, the upper arm X-axis angle, upper arm Y-axis angle, and upper

arm Z-axis angle were calculated, these being defined relative to an inertial moving

coordinate system, with origin that was attached to and moved with the shoulder at the

acromion and axes that remained directed as and parallel to those of the FOB transmitter.

]Go to Top of Document[

Fig. 1. Instrumentation of the subject with the FOB receivers and the APAS reflective

markers.

446

Eckhouse,

Penny, and Maulucci

Level IV

consisted of a human subject making a simple three-dimensional functional reach. The basic

reach, targets, and instrumentation were as defined for Level 111. The reach was made

during the 6-sec data collection interval. During this interval, the x, y, and z

translation trajectories of the end effector, wrist, elbow, and shoulder were obtained.

Trajectories for the wrist flexion/extension, wrist radial/ulnar deviation, forearm

pronation/supination, elbow flexion/extension, upper arm Xaxis, upper arm Y- axis, upper

arm Z-axis, and shoulder medial/lateral rotation angles were also obtained during the

6-sec interval. Graphs for all trajectories during the actual movement time, i.e., the

time from the initiation of arm movement to the touch of the target, were produced.

Eighteen targets, differing in location or final position required, were used.

Several types of analyses were performed on the data acquired with the

manual system, the FOB, and the APAS in the four-level testing. It was necessary to limit

the number of trials for incorporation into the analyses because the APAS data were

manually digitized which is an extremely time-consuming process for this type of

application. Representative trials were randomly selected from each level or sublevel.

Table I gives measurement values obtained from Level I testing for the

measuring tape or goniometer (referred to as the manual system), the FOB, and the APAS.

The x, y, and z values (centimeters) are for one arbitrarily selected trial of Level I.A.

They are calculated by taking the average of the three tape measure

]Go to Top of Document[

(Degrees) for the Manual System, the FOB, and the APAS

Angle (Degrees), and a Fixed Twist Angle Displacement

Between Two Fixed Points (Centimeters), a Fixed Flexion

I. Measurement Values of the Translational Distances Table

447

Instrument Comparison

| |

Manual System |

FOB |

APAS |

| x |

37.4 |

37.7 |

37.5 |

| y |

55.9 |

56.1 |

55.6 |

| z |

20.0 |

21.0 |

20.5 |

| Flexion Angle |

135 |

135 |

135 |

| Twist Angle |

46 |

47 |

47 |

frames. The flexion

angle values (degrees) are for a trial in Level I.B in which the goniometer was

perpendicular to the ground, but at a 45 degree angle outward with respect to the APAS

cameras. They are calculated by taking the average of the three goniometer readings, all

of the FOB samples, or all of the APAS frames. The twist angle values (degrees) are

calculations of the displacement angle for a trial in Level I.C in which the goniometer

was rotated and tilted relative to the plane of the APAS cameras. They are calculated from

the average of the three goniometer readings, all of the FOB samples, or all of the APAS

frames for each of the two composite angles. A one way analysis of variance applied to the

five values obtained with each of the three techniques revealed no differences in the

means among the manual system, the FOB, and the APAS (p > 0.05). 360 APAS ments, the

average of the 600 FOB samples, or the average of the

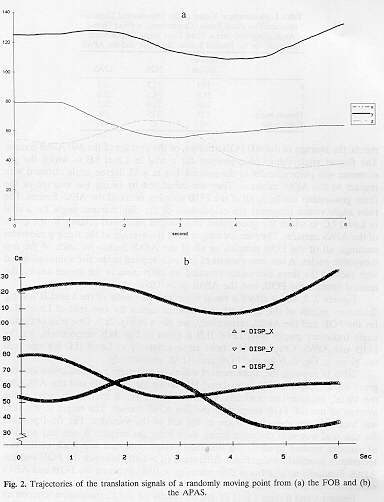

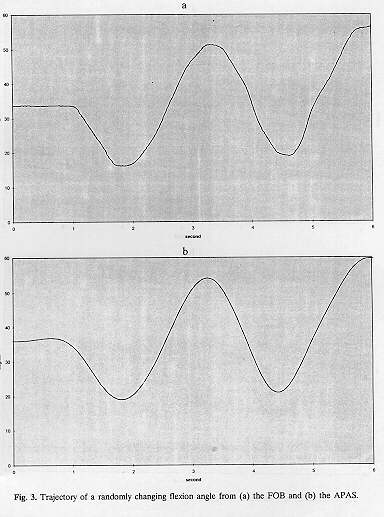

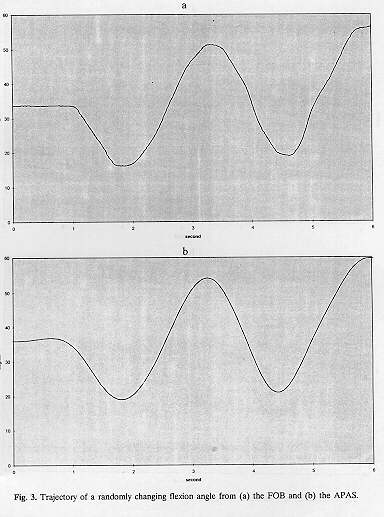

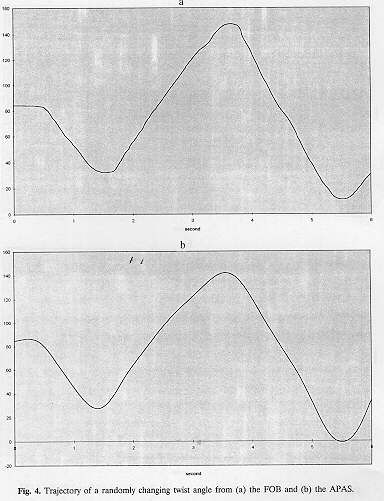

Figures 2, 3, and 4 afford a visual inspection of results of the Level

II testing. Trajectory graphs of the

Y,

y, and z translation signals for

one trial of Level II.A for the FOB and the APAS, respectively, are given in Fig. 2a,b.

One trial of flexion angle trajectory graphs from Level II.B is given in Fig. 3a,b,

respectively, for the FOB and APAS. Graphs of the twist angle trajectory at Level II.C for

one trial are given in Fig. 4a,b for the FOB and APAS, respectively.

Table Il contains the measurement values (centimeters for translations

and degrees for angles) obtained from Level III testing for the FOB and the APAS for the

initial, intermediate, and final positions of one reach trial. Each value is the average

of the 600 FOB samples or the 360 APAS frames. The target in this trial was located 8 cm

above and 8 cm to the left of the shoulder. The final position for this trial was with the

palm facing away from the subject. A one way analysis of variance applied to all of the

translation values obtained with each of the two techniques revealed no significant

differences (p > 0.05) between the FOB and the APAS. Similarly, no significant

differences (p > 0.05) between the FOB and APAS were observed for the angle values.

Figures 5 and 6 show Level IV testing results for the 12 translation trajectories and the

eight angle trajectories. Graphs for one trial from one subject are shown in Fig. 5a-d

for the FOB translations and angles and the APAS translations and angles,

respectively. The target in this case was located at shoulder level and 16 cm, to the

right of the shoulder, with a final position of the palm facing toward the subject. Figure

6a,b, respectively, for translations and angles, shows this same trial as the FOB values

plotted against the APAS values during the movement time. Specifically, for each point

during the movement time of the reach, each of the 12 APAS translation values is paired

with the corresponding FOB translation value and all pairs plotted on the same graph;

similarly, for each sample, the eight APAS and corresponding FOB angles are paired and

plotted on a second graph. These graphs offer a further examination of the similarity of

the two systems, in that the closer the data points in the graphs can be fitted by a

straight line with slope 1, the more alike are the values of the two systems.

Fig. 2.

Trajectories of the translation signals of a randomly moving point from (a) the FOB and

the APAS.

]Go to Top of Document[

Instrument Comparison 447

ments, the

average of the 600 FOB samples, or the average of the 360 APAS frames. The flexion angle

values (degrees) are for a trial in Level I.B in which the goniometer was perpendicular to

the ground, but at a 45 degree angle outward with respect to the APAS cameras. They are

calculated by taking the average of the three goniometer readings, all of the FOB samples,

or all of the APAS frames. The twist angle values (degrees) are calculations of the

displacement angle for a trial in Level I.C in which the goniometer was rotated and tilted

relative to the plane of the APAS cameras. They are calculated from the average of the

three goniometer readings, all of the FOB samples, or all of the APAS frames for each of

the two composite angles. A one way analysis of variance applied to the five values

obtained with each of the three techniques revealed no differences in the means among the

manual system, the FOB, and the APAS (p > 0.05).

Figures 2, 3, and 4 afford a visual inspection of results of the Level

II testing. Trajectory graphs of the x, y, and z translation signals for one trial of

Level ILA for the FOB and the APAS, respectively, are given in Fig. 2a,b. One trial of

fleidon angle trajectory graphs from Level ILB is given in Fig. 3a,b, respectively, for

the FOB and APAS. Graphs of the twist angle trajectory at Level II.C for one trial are

given in Fig. 4a,b for the FOB and APAS, respectively.

for

the initial, intermediate, and final positions of one reach trial. Each value is the

average of the 600 FOB samples or the 360 APAS frames. The target in this trial was

located 8 cm above and 8 cm to the left of the shoulder. The final position for this trial

was with the palm facing away from the subject. A one way analysis of variance applied to

all of the translation values obtained with each of the two techniques revealed no

significant differences (p > 0.05) between the FOB and the APAS. Similarly, no

significant differences (p > 0.05) between the FOB and APAS were observed for the angle

values.

APAS Table II contains the measurement values (centimeters for translations

and degrees for angles) obtained from Level III testing for the FOB and the

translations

and angles, respectively. The target in this case was located at shoulder level and 16 cm

to the right of the shoulder, with a final position of the pahn facing toward the subject.

Figure 6a,b, respectively, for translations and angles, shows this same trial as the FOB

values plotted against the APAS values during the movement time. Specifically, for each

point during the movement time of the reach, each of the 12

and the APAS Figures 5 and 6 show Level IV testing results for the 12 translation

trajectories and the eight angle trajectories. Graphs for one trial from one subject are

shown in Fig. 5a-d for the FOB translations and angles

Fig. 3. Trajectory of a randomly

changing flexion angle from (a) the FOB and (b) the APAS.

Table III is a chart of a

statistical analysis of the Level IV results over all six subjects for the target just

defined. Six subsets of the set of 20 translation and angle trajectories were selected,

these being the end effector translation; elbow translation; all four joint translations

taken together; elbow flexion/extension angle; upper arm X, Y, and Z axis angles; and all

eight angles taken together. For each

subset, the signed difference

between corresponding FOB and APAS values for each sample during the movement time of the

reach trial for every subject was calculated. Descriptive statistics of mean, median, and

standard deviation were applied to these differences, for each subset. A mean close to 0

implies that there is no bias between the two systems in that it indicates that neither

system is consistently operating at a higher or lower range than the other, although it

does not necessarily signify that

Instrument Comparison 451

]Go to Top of Document[

the differences between the system values are small. Finally, a

reliability coefficient(18,19) was calculated for each subset, using the actual

measurement values given by the two systems. This coefficient, ranging from

0.0 to 1.0, is a measure of the capability of

the FOB and APAS to produce the same value when operating under uniform conditions, with 1.0

indicating perfect reliability.

DISCUSSION

The FOB and

the APAS have been compared under different conditions of operation. In Level I, it was possible to evaluate these two instruments

against traditional devices used in conventional anthropometry, namely, the steel

measuring tape and the plastic goniometer, thus allowing the results to be considered with

respect to commonly accepted actual values. In general, however, since there are no

standard kinematic instruments with which to validate the results, this study investigates

how close the performances of the FOB and APAS are to each other, rather than how close either is to the true physical

measurement.

Level

I, the easiest level in which to obtain system

compatibility since it deals with rigid bodies and no motion, shows the FOB and APAS to be operating close to each other and close to the actual physical

measurements. Level II becomes more difficult with the introduction of motion. However, the systems are still operating with visually comparable

results for both translation and angle trajectories. Level III introduces to the systems

the complexities in dealing with the human body. Nonetheless, the FOB and the APAS still show no significant incompatibilities in this static case. This is

particularly impressive since due to the inherent operation of the two systems, they do not always calculate from the same quantities

when used with a human subject. For example, a tilt in the receiver caused by the slants

and contours of the body segment to which it is attached will

influence the angle

and Degrees for Angles) for Functional Reaches From Six Subjects

Table III. Statistical Analysis of the FOB and APAS Differences

(Centimeters for Translations

455

Instrument Comparison

End effector translation

1.22

0.88 1.94 0.997

Elbow translation

-0.07

-0.03 1.48 0.999

All joint translations

0.12

0.20 2.12 0.998

Elbow flexion/extension angle

4.17

6.11 5.82 0.954

Upper arm X-, Y-, Z-axis angles

2.67

2.47 4.28 0.991

All joint angles

4.33

3.29 15.49 0.980

Mean Median SD Reliability

measured by

the FOB. Furthermore, the anatomical angles do not correspond to the Euler angles that are

directly collected by the FOB, and must be calculated, often from more than one receiver;

slight misalignments, can impact on these calculations. With regard to the APAS, misses in

the location of the joint center on the limb segments, with either manual or automatic

digitizing, will influence the angle measurements. Finally, for the FOB, the joint angles

are calculated from angle values, whereas for the APAS they are calculated from positional

values of the vertex and sides of the angle; thus, numerical discrepancies might be

expected to arise from the mathematical calculations.

At Level IV, the full array of complicating factors inherent in the

human body are present. Issues such as skin rotations, muscle activity, and tissue masses

all have the potential to contribute errors in the acquired data and challenges to system

compatibility. From the graphs, it can be observed that the shapes and displacements of

corresponding signals are quite similar. The reliability coefficients indicate that

overall the systems produce close results for both translation and angle trajectories.

to attain the same measurement. With this exception, however, any

differences are due to the basic operation of the systems, and not to discrepancies in

signal processing algorithms or routines. FOB and

APAS data It is important to note that the data were taken from the systems at

the most rudimentary level of each system, prior to the application of any system analysis

software, and then processed using the same analysis software in both cases. In

particular, the FOB data were taken as the x, y, z locations and the a, e, r angles of the

receivers, and the APAS data were taken as the x, y, and z locations of the end effector,

wrist, elbow, shoulder, and stenoclavicular joint, and of the two reflective bans on the

forearm and the upper arm crosspieces. Both sets of system data were then analyzed by the

same software to derive the x, y, and z translation trajectories of the end effector,

wrist, elbow, and shoulder, and trajectories for the wrist flexion/extension, wrist

radial/ulnar deviation, forearm pronation/supination, elbow flexion/extension, upper arm

X-axis, upper arm Y-axis, upper arm Z-axis, and shoulder medial/lateral rotation angles.

As explained above, the nature of data required different calculations on the

It may be concluded that the electromagnetic tracker and video

motion analysis systems perform closely enough on static inanimate objects to allow

quantitative data to be compared, and permit dynamic inanimate objects to be compared

qualitatively. The systems present no problems for the static animate case, and can be

used interchangeably. Qualitative comparisons can be made in the dynamic animate case, and

for studies interested in basic trajectory shapes and displacements the two systems are

demonstrably comparable.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Gideon Ariel for his extensive technical

assistance in adapting the Ariel Performance Analysis System for this study. This work was

supported by NASA contracts NAS9-18514 and NAS9-18915.

]Go to Top of Document[

REFERENCES

Industrial

Ergonomics and Safety II, Taylor & Francis, pp. 301-308, 1990. Advances in 2. Tyson, J.N., and Das, B., A comparative analysis of anthropometric

and kinematic measurement systems. In (B. Das, ed.),

1. Ayoub, M.M., Human movement

recording for biomechanical analysis. Int. J. Prod Res. 10(l):35-51, 1972.

Biology Society, 13-17,

1985. Medicine and Engineering in of the IEEE Annual

Conference Proceedings of the Seventh 3. Logan, S.E., Vannier, M.W., Bresina, S.J., and Weeks, P.M., Wrist

kinematic analysis using a 6 degree of freedom digitizer.

11. Maulucci, R.A., Optimal Workspace Design. Technical Report, National Aeronautics and

Space Administration, Contract NAS9-18514, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX,

1993.

88-91,

1986.Design News

10. Bak, D.J., Electromagnetic monitoring quantifies motion behavior.

9. Diener, H.-C., Bacher, M., Guschlbauer, B., Thomas, C., and Dichgans, J., The

coordination of posture and voluntary movement in patients with herniparesis. J. Neurol.

240:161-167, 1993.

11:55-60,

1992.Med. Biol. Eng. IEEE

8. Bravo, 0., Angular levers and power in the human body.

4:73-79, 1989.Biomech.

7. Pearcy, M.J., and Hindle, R.J., New method for the non-invasive three dimensional

measurement of human back movement. Clin.

-81,

Paper #88-0211, 1988.Proceedings 75

6. Logan, S.E., Groszewski, P., Krieg, J.C., and Vannier, M., Upper extremity kinematics

assessment using four coupled six degree of freedom sensors. ISA

1(7):613-620, 1988.Biomech. 2

5. An, K.-N., Jacobsen, M.C., Berglund, L.J., and Chao, E.Y.S., Application of a magnetic

tracking device to kinesiologic studies. I

4. Bresina, S.J.,

Vannier, M.W., Logan, S.E., and Weeks, P.M., Three-dimensional wrist imaging: Evaluation

of functional and pathologic anatomy by computer.Chn. Plast. Surg. 13(3):389-405, 1986.

12. Maulucci, R.A_ Nonstandard Functional Limb Trajectories. Technical

Report, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Contract NAS9-18915, Lyndon B.

Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX, 1995.

ng. 2(3):147-157, 1994. Rehab. ETransact. IEEE

13. Eckhouse, R.H., Leonard, E.L., Zhuang, Q., and Maulucci, R.A.,

Improving reaching in preschool children with cerebral palsy through regulated feedback.

tat. 29:209- 211, 1958.Math. S

19. Olkin, I., and Pratt, J.W., Unbiased estimation of certain correlation coefficients.

Amer.

Clinical Erperiments, John

Wiley and Sons, New York, 1986.of Analysis The Design and

18. Fleiss, J.L.,

19(2):147- 166, 1987.Behav.

17. Fetters, L., and Todd, J., Quantitative assessment of infant reaching movements. J.

Motor

ng. 28(5):411-416, 1981.Biomed. ETransact IEEE

16. Sherif, M.H., Gregor, R.J., and Lyman, J., Effects of load on myoelectric signals: the

ARIMA representation.

15. Flanagan, J.R., and Rao, A.K., Trajectory adaptation to a nonlinear visuornotor

transformation: evidence of motion planning in visually perceived space. J. Neurophysiol,

74(5):2174-2178, 1995.

14. Isenberg, C., and

Conrad, B., Kinematic properties of slow arm movements in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol.

241:323-330, 1994.

]Go to Top of Document[

[Back to Home Page]